I. PHILOSOPHICAL PART

In my last article on memes, we busted free will a bit and considered all sorts of possible and impossible concepts of consciousness. We discovered that “morf” is practically the same in the meme world as DNA is in the molecular world. We discovered that morf is the code for the creation of a meme in a human head. Thus, it has no intentionality of its own, but instead is merely a manifestation of the intentionality of life in human heads. In short, then, the morf is something like an amazing dimensional protocol that allows the transfer of data from the dimension of one head to the dimension of another head through the dimension of the physical space between the heads.

And since we got a bit philosophical about some of that god stuff in the last article, we could ultimately theoretically equate every single meme to a god. Every single meme is a god because it represents an intention in the brain of the memebiont (human). An unbreakable pattern whose intention (replication) must be fulfilled by the creation of an idol for a god (morf). Once a god does not have enough idols, it cannot replicate. And such a god will die.

And after dead gods, there is a lot of mess left in the form of idols that have lost their replicative purpose. The idols have become mere artifacts, and now we can only guess which dead gods they belong to. And in the process, new idols are born, new gods are created and disappear, and they have all kinds of clashes, synergies and so on with each other. So the sapients live in an infinite entropy of gods whether they admit it or not.

II. PRACTICAL PART

The metabolism of morfs

But let’s bring our feet back down to earth and try to think a little less philosophically and a little more factually about this whole issue and its consequences.

Thanks to the fact that our dear idol (morf) has no intentionality, but is merely a manifestation of the intentionality of god (meme), we might well deduce that, for example, such an AI – which we will discuss a bit more in the next article – is also a morf. A morf that has no intentionality of its own, that is not alive and therefore cannot replace anything alive.

Unfortunately, it is not that simple.

For AI, the key is precisely that the morf is merely an idol and not a god. The morf is not part of the memebiont. And that’s a big difference from such organic life, where DNA is always part of the organism’s body in some form, especially when it’s functional. But the morf always operates outside the body of the memebiont, even outside the body of the sapient in whose brain the memebiont lives. And this specificity of the morf has several implications that make it fundamentally different from DNA, and thus come with a completely different evolutionary context than what we humans are used to in the organic world.

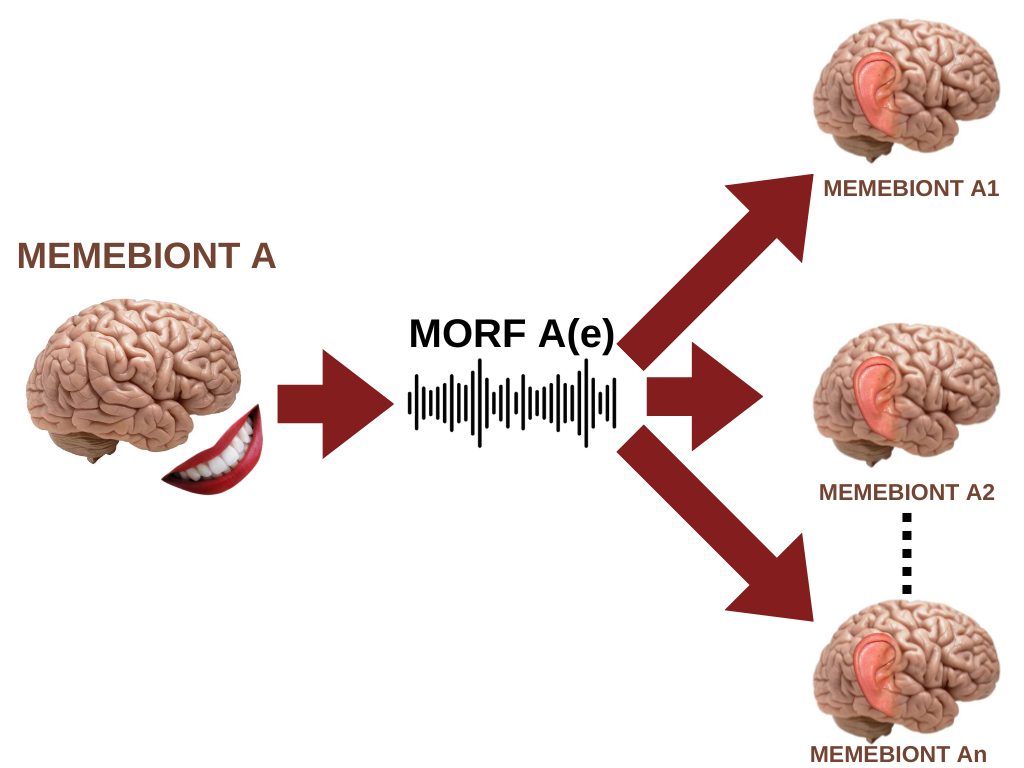

One of the consequences is the so-called replicative mutiplicity. And what exactly is that? Well, in the last article we saw an example of a morf that was created precisely when a memebiont created it in the form of speech. The morf that was created that way then caused the same memebiont to replicate in another brain. However, the same morf can simultaneously cause replication of memebionts in many brains at the same time, as we can see schematically shown in the following figure:

Replicative morf multiplicity is of course a huge advantage for any memebiont that can create morfs that can simultaneously act via the sapient senses (such as hearing and sight) directly on the input sensory centers of multiple brains simultaneously. And here it is important to note precisely that such a morf lacks all three properties of life – metabolism, replication, and intentionality. The morf neither changes nor replicates during memebiont replication, nor does it have any self-interest or need. As mentioned above – it is merely an empty idol for a god who is not necessarily alive at the time of the morf’s existence.

The great disadvantage of a sonic or visual morf is its immediate extinction after the act of replication. Such morfs were named by my friend Daimonion as “ephemeral morfs” (from the Greek ephemera (ἐφήμερα), epi (ἐπί) – “on, for” and hemera (ἡμέρα) – “day”). Although replicative multiplicity increases the chances of survival for those memebionts that can cause it, the consequence is uncertainty in the shape stability of their descendants. The variability of descendants can be high and is limited only by the size of the population of brains. The larger the population, the greater the variability. The original memebiont alone can’t do much about it. The morf is outside its body and is temporary. Natural selection determines the only way to stabilize it. Such variants that deviate too far from the Gaussian normal probability distribution have a diminishing chance of succeeding in existing memebiont brain ecosystems. They lose what in semantics is called “understanding what is being said”. Or in other words – the idol of god becomes an artifact because god is dying.

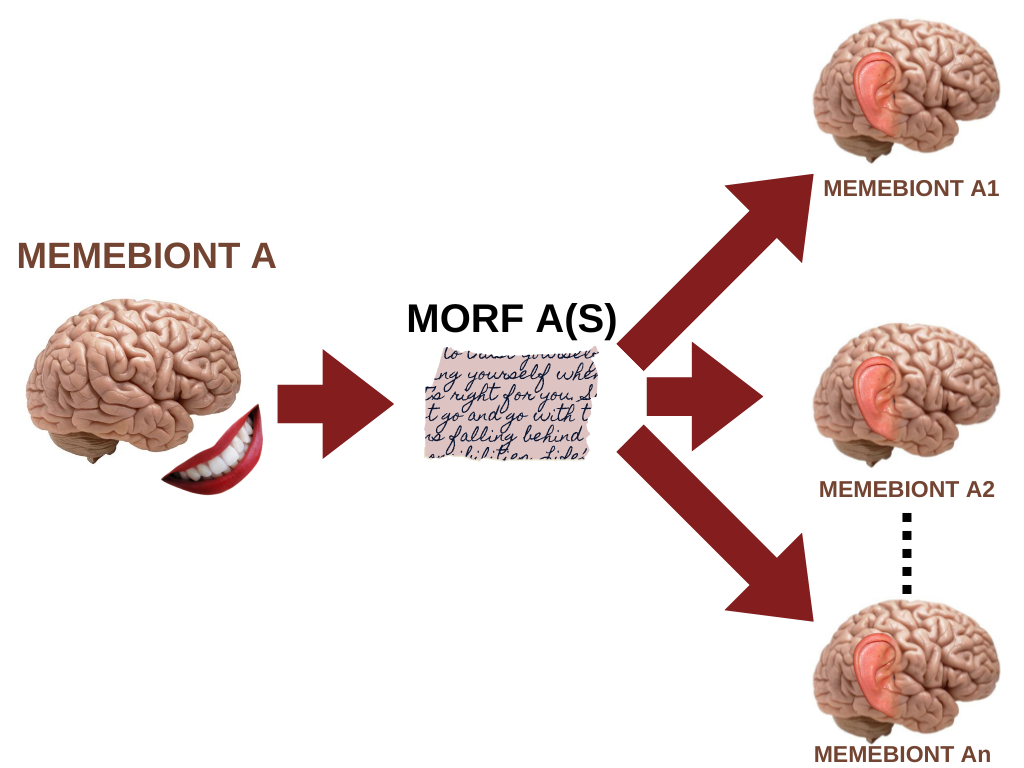

All the drawbacks of such morfs must have sooner or later inevitably led to the evolution of such memebionts, which produce other, more antifragile types of morfs for their reproduction. My friend Daimonion called them “solid morphs” (from the Latin solidus = solid substance). In the following figure we see an example of such a morf – writing:

Thanks to the solid morfs, we learn about the earliest manifestations of the memeosphere, for example in cave paintings or stone sculptures or buildings. The solidity of these morfs dramatically increases the chances of memebionts to be replicated not only within space but also within time. For our article, it is important to note, first of all, that these morfs themselves have none of the three properties of life – that is, their lifespan is precisely in the brains where their memebionts live.

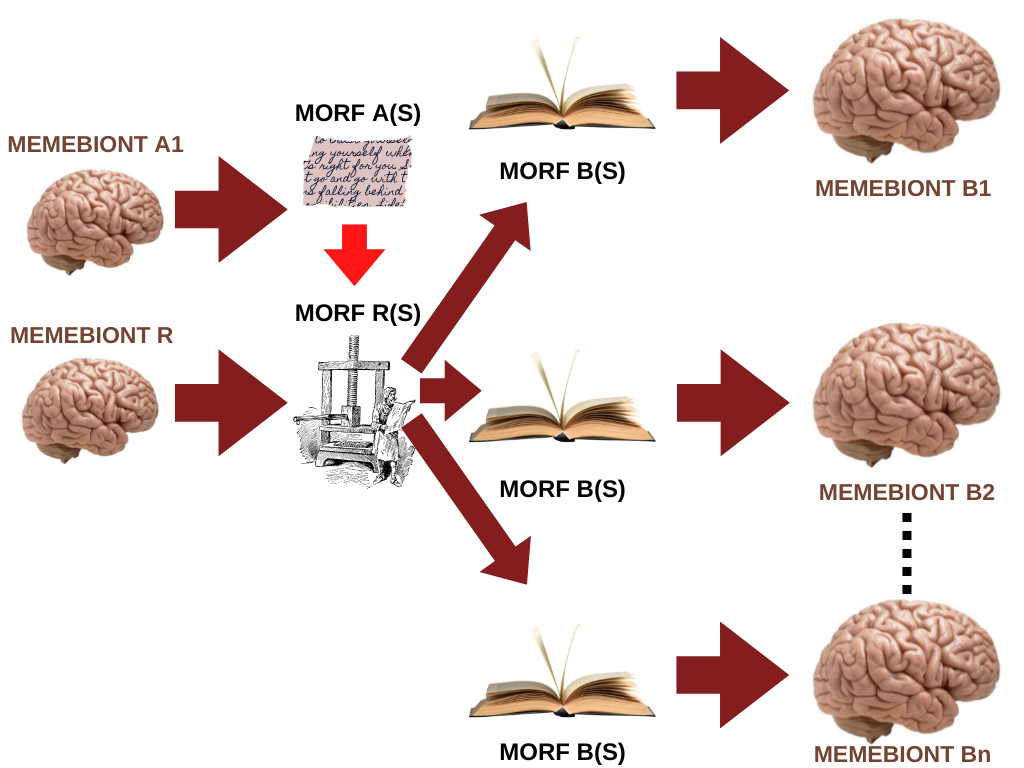

However, the separation of morfs from their memebionts into different environments has given us all sorts of separate processes for memebionts and for their morfs, including evolutionary processes. Consider the situation in our third figure, where we see Gutenberg’s bookplate. The memebiont in the brain of the author A1 is trying to replicate via the solid morf A(S). However, it does not do this step directly but through the solid morf R(S), which serves as a replicator. And this replicator is the product of another meme in the brain of the book printer. The result is books, i.e., solid morfs of B(S). Thus, morf B(S) is a metabolite of morf A(S) because morf A(S) is a variable of morf B(S), as shown by the red arrow.

Well, this is quite a fundamental change in the situation. Metabolization of A(S) to B(S) may or may not take place via memebionts in the brain of the book printer. A book printer can metabolize A(S) to B(S) by hand (by writing individual letters on individual pages), but today it can also be done entirely without the contribution of such a step – for example, by purely printing out text written on a computer using a printer. The key here is the morf R(S), which performs this metabolic step. And not only that. Morf R(S) also replicates morfs B(S), so that the whole system of morfs A(S) and R(S) satisfies the two properties of life – metabolism and replication.

But what about intentionality? The A(S) morf is indeed metabolized to the B(S) morf, but it does not itself make any decisions about it. All the decisions of these processes come from the brain of the author and the brain of the book printer, in which the A and R memebionts have intentionality. Any deviation from the interests of these memebionts is, in the name of their intentionality, corrected in all sorts of ways so that memebiont A replicates itself as closely as possible to memebiont B. The whole system of morfs A(S) and R(S) is thus lifeless and still only a passive executor of the intentionality of the memebionts in the brains, like a spider releasing the digestive juices of its insect prey and leaving its metabolism to a space outside its body.

Morphs with replicative multiplicity and the ability to metabolize other morfs are surprisingly abundant. For example, harvesters, internets, atomic reactors, mediums, and so on. And we’ll discuss whether these include AI itself in the next article on memes 🙂