You were not there for the beginning. You will not be there for the end. Your knowledge of what is going on can only be superficial and relative.”

William S. Burroughs

Meditation is a very strange phenomenon. It is no longer the privilege of half-naked exots from the Himalayas or hippies (pretending to be half-naked exots). Meditation as a practice has fully entered western society and is used to hack stress, attention, and life itself. Google pays its employees to practice meditation due to the fact that it increases their productivity, people around the world download meditation apps (such as Calm), and with all of this, everyone around asks basic questions like “how to meditate” or “which specific meditation technique to use”.

Honestly, I don’t answer any of these questions for safety reasons. The brain is punk and everyone’s punk is a little different. Therefore, different techniques and methods are automatically suited to each of us to achieve the desired state of being.

The question “how to meditate” is basically the same as the question “how to be healthier” for me. Both, in short, depend on the parameters of the body we are working with – first of all, we need to know what specifically we are not healthy in and what specifically we are not “meditative” in.

Much more useful than giving some verbal instructions on “how to meditate”, from my point of view, is to point out the classic mistakes that many beginning meditators make, and in doing so to reflect on “how not to meditate”, what meditation actually is and what it does to our experience of reality. And above all, why meditation is so cool in the first place.

And that’s exactly what this blog will be about.

Pink Elephant

My dad used to tell me a story about a guy who wanted to brew an extremely mystical and mysterious concoction. But there was a catch. The guy couldn’t think of a pink elephant while he was brewing it. As soon as he thought of the pink elephant, the recipe for the mystical mysterious concoction failed. And that’s why that concoction has never been made anywhere in the history of mankind.

Apparently, my father told me this story in order to point out the paradoxical nature of the human brain and, above all, the senseless conflicts that arise within it.

Once the recipe for the mystery concoction is spiced up with a condition (not thinking of the pink elephant), my brain will iterate the concept of the recipe given the condition whether the brain wants it or not.

And why do I mention pink elephants and mysterious mystical concoctions anyway? Because it’s undoubtedly related to meditation!

As I mentioned before, many people make beginner mistakes when meditating. And the most classic beginner’s mistake is just trying to “think of nothing.”

And where is that mistake? Well, meditation is a kind of strange, intentionless state of consciousness that is quite difficult to describe. But more importantly, “thinking of nothing” is also just an intention, and with intention the brain cannot meditate. If I am thinking about thinking of nothing, I am thinking about something after all. It is, in short, intention for the sake of getting rid of intention. And intention for getting rid of intention is just a fancy name for “don’t think of the pink elephant.”

There are different types of meditations, such as mindfulness, which tries to direct your attention to your breath, or gratitude, which tries to direct your attention to some specific thoughts and their specific meaning. The interesting thing is that all of these types of meditations try to create a kind of auxiliary intentions in our brains, in the sense of “try to think about this and that” or “notice this and that”, which will eventually dissolve and help us get into a state of meditation. The important point, however, is that the end product of all meditation practices should not be an intention, but its opposite.

The phenomenal Indian guru Osho, for instance, compared meditation to walking on a tightrope – walking on a tightrope feels great, but it is very unstable and you can easily fall off the tightrope at any time.

Osho’s language is very close to my heart. This cool dude even talked about intentions, among other things, as he described meditation as a state in which “we do nothing and just exist”. It is simply a state in which all our plans, fears, joys and ultimately all thoughts completely disappear and we feel ourselves as just some simple consciousness that is drifting in the void. Most importantly, the thoughts don’t go out of our head because we command them to.

As mentioned earlier, the brain is punk. And when punk wants to be meditative, we can’t expect it to iterate through a task. Punk needs to be left alone and only then can it start idling. That’s why the meditative state reminds me so much of childhood experiences when I used to go on holidays to Greece and spend the whole day getting carried away and beaten by the waves of the Aegean Sea. The interesting thing about all of that was that my brain somehow transformed this day-long experience into a strange state of consciousness that would emerge as I fell asleep after an exhausting day in my hotel room. At the time, I had the feeling that my consciousness was somehow being lifted and tossed around by the waves. And it was something I could almost physically feel, but it was only in my head. It reminded me of dreaming, even though I wasn’t completely asleep and I was still able to perceive environmental stimuli, such as people’s conversations. In short, my brain was idling; processing the day’s experiences, all sorts of mixing and metamorphosing them without anyone correcting it. And during all this I felt an amazing relaxation, despite the fact that sometimes an illusion of a wave made me think that I was really in the waves, and I therefore came out of this strange state of consciousness and opened my eyes 🙂

But this strange “idle” state can be achieved by other practices than meditation or falling asleep after a day in the Aegean. I also experience it during various breathing exercises (e.g. Wim Hof), during psychedelic experiences, and in some microdose, various nutritional supplements and adaptogens help me to integrate it into my life.

But let’s stay with meditation as something that consists only in systematically developing the ability to register (and therefore change) our actual experience without external stimuli or exercises. Thus; let us stay with meditation as pure headwork. Neither Wim Hof, nor psychedelics, nor adaptogens change our lived experience by themselves. They are merely tools, and their interaction with our brains is necessary for their functionality.

Especially with psychedelics, the observation of our experience is so highly amplified and manifested by archetypal symbolism that it can be quite challenging and exhausting for an inexperienced person to understand “what’s really going on in my brain” and “what my brain is trying to tell me”. But we’ll talk a bit more about the psychedelic experience in just the second blog in this series.

Micro-Idles in Ordinary Life and the New Brain

The more we expose ourselves to altered states of consciousness, and importantly – the more we become aware of what is happening (i.e. meditate) – the more we can see the consequences of integrating such changes into our ordinary life. The way we perceive reality changes.

Depending on how much our worldview is changed, I would venture to divide the meditative transformation of the brain into the following two phases:

PHASE 1 – Observation of the Old Brain

When we are exposed to a strong intention, in most cases it is a strong emotional reaction that prompts us to act. Imagine, for example, an angry person who can be seen on the street, swearing vulgarly at someone. Let us imagine that such a person has never heard about meditation in his life. Somehow, therefore, he doesn’t really address why he is just angry, what anger brings to him, or whether he even wants to spend his current time in anger. Such a person is simply consumed by his emotion. His brain doesn’t surf on idle waves, but creates tasks and forces the body to react immediately and mindlessly.

It is the Old Brain, and I have ventured to name its bearers as HOS (Homo obsoleta solicitus). Such people and such brains make up the majority of our population and therefore make up the majority of the society in which we live.

But let us not be critical. All of us have certainly at least once in our lives acted like HOS and been a carrier of an Old Brain. However, once we meditate and become aware of the connections, a very significant change takes place.

Well, let’s imagine our angry man in the street again. This time, however, he has been somehow meditative and thus his way of perceiving reality has changed. Instead of “I am angry”, this time our man feels something like “I observe that I am angry”. And this is a fundamental difference!

What has actually happened in our man’s brain? Well, we already know that during meditation we experience a kind of “idling”, but the visible change takes place only when we can integrate this idling in some micro-form into our ordinary life. Such micro-idling in ordinary life is certainly not as intense and fulfilling as the idling we experience while meditating with our eyes closed (since it is micro), but it has the same qualities. It frees us from intentions and creates a kind of “space” between what we observe and what we experience.

A person who observes his emotions in this way can then find it easier to understand them and realise some of the connections. After a few seconds, our angry little man may reflect on the source of the anger he is observing, and then he can “dissolve” the intention of anger, just as meditation can “dissolve” any other intention in the brain. Our angry person has integrated meditation into his life, and with a little compassion, he may be able to explain his vulgar behavior to the person he was arguing with, and understand his perspective on the situation 🙂

Such a brain is the New Brain and I have ventured to name its bearers as HNE (Homo Novus Excitavitus). Such people and such brains are a minority in our population.

As a child I was an optimist and thought that a person can only transform from HOS to HNE and transformation in the opposite direction is not possible, but now I know that this is not the case. Both types of brains interact and influence each other to a greater or lesser extent. And it can’t be caused by anything but memes and their own intentionality.

Jaggi Vasudev (Sadhguru), probably the most prominent half-naked Himalayan exotic of our time, compared the difference between the Old Brain (the brain without space) and the New Brain (the brain with space) to a traffic jam – if I observe a traffic jam from some distance, for example, from space, the traffic jam doesn’t annoy me as much as if I am sitting behind the steering wheel of one of the cars that are stuck in the traffic jam. I just enjoy flying in space and watching all those angry drivers with detachment and a sense of curiosity.

PHASE 2 – Observation and Creation of the New Brain

The “space” between the observed and the experienced, created by the integrated micro-idles within us, undoubtedly allows us to experience and observe things differently. If our man, whom we imagined, often encounters the intention of anger when experiencing some situation and regularly “dissolves” it, he also creates new intentions and incorporates them into his normal functioning. The feeling of “I observe that I am angry” is deepened into a feeling of “I observe” or is replaced by a feeling of “I observe something different from anger”.

For example, an interesting state is also what I would describe as “I observe, but there is nothing to observe”, which can occur during very deep meditation or psychedelic experiences, and this phenomenon is professionally known as ego-death. In any case, it is a very transformative and difficult to describe experience that can open up existential questions such as “do we even exist anymore when there is nothing to observe” (hence the death of the ego). And it’s especially interesting when this state appears out of nowhere without any meditation; or appears out of nowhere while we are engaged in the ordinary activities of life. Some mystics call this remarkable state “enlightenment” (but it can also be a simple psychosis), but (maybe) we’ll talk about that some other time.

Meditation from a neuroscientific perspective

Is there a scientific explanation for such changes in our brains? Of course. Even our beloved Osho – despite being Indian, wearing a long beard and claiming to be a guru – distanced himself from all religions, superstitions and other esotericisms. He claimed that “metitation is primarily a matter of science”.

Unless science is exactly your friend and you are a bit disoriented in biological terms, feel free to skip this part of the blog.

Neuroplasticity

A key driver of change in the brain is the term ‘neuroplasticity’, which essentially refers to the brain’s ability to change and adapt throughout life.

Thanks to neuroplasticity, we know, for example, that if our brains are not exposed to certain types of sensations at a certain critical period, they cannot develop the ability to process those sensations later on. For example, little cats that grow up in the dark cannot learn to recognize visual sensations after a certain period of time. Young children who do not have the opportunity to learn speech do not master it later or master it only very imperfectly. Of course, the brain also changes in adulthood – for example, our ability to remember specific episodes and general meanings is a consequence of neuroplasticity – we know, for example, that experts (chess players, musicians, taxi drivers) have parts of the brain that are involved in their particular skills more developed than the average random person.

The brain is also able to compensate for damage by having some parts of it take over the functions of the damaged parts to some extent. As with meditation, self-effort is important (which is applicable to neuroplasticity in general). People after a stroke who train systematically are able to replace their lost abilities more quickly and to a greater extent.

However, character traits, attention, ability to control emotions, etc. are mostly considered permanent and stable traits. Neuroscientists have theorized that after a critical period, these traits no longer develop in the brain and only degeneration occurs due to aging. However, research into the effects of meditation on brain structure and function shows that these characteristics and the areas of the brain that are related to their expression may also change.

Some of the effects of meditation on brain structures and functions found so far

In this section, we will discuss just a few of the most important findings in the relationship between meditation and structural and functional changes in the brain. Every month there are several new articles and studies on this topic, so I do not think it will be effective to mention here some of the hot news.

The first evidence of cortical plasticity related to meditation practice was provided by Sara Lazar’s team (Lazar et al., 2005). Based on previous studies showing that meditation induces lasting changes in the EEG, Sara began research with 20 subjects who practiced mindfulness and insight meditation (satipatthana-vipassana) for a long period of time (average 9 years, 6 hours per week). Using magnetic resonance imaging, they investigated the strength of their cerebral cortex. Compared to the control group, the meditators were found to have increased cortical strength in areas involved in attention, perception of internal states, and processing of sensorimotor stimuli. The increase in cortical strength was greater just in the elderly, suggesting that meditation may slow the natural cortical decline caused by aging.

Another team (Brefczynski-Lewis, Lutz, & Davidson, 2004) followed a group of long-term (thousands of hours) practicing Tibetan monks. The research focused on functional changes during active practice of two types of meditation. The control group consisted of people who had never meditated before and only received meditation instruction shortly before the test. Compared to the control group, people practicing “visual object focusing meditation” were found to have increased activity in the frontal and parietal lobe regions involved in maintaining attention. In “compassion without discrimination” meditation, in which the meditator attempts to “broadcast” a feeling of compassion, increased activity was found in areas related to perceiving the state of self and others, planning of movements, and positive emotions.

Interestingly, one of the components of meditations that develop mindfulness is a kind of verbal labeling of experienced content, including emotions. The verbal labeling of the experience surprisingly enables a greater “micro-idling” and thus a greater “space” between the observed and the experienced, and thus a greater level of coping with the experience. A study (Creswell et al., 2007) looked at subjects who, although not meditating, were found to have varying degrees of mindfulness, or ‘micro-idle’, based on specialised questionnaires. Subjects then marked projected faces with emotionally charged expressions. They either labeled these emotions directly or also identified the gender of the face in a control task. Research showed that higher mindfulness was related to higher prefrontal cortex activity and lower bilateral amygdala activity when labeling emotions compared to the control gender-determination task. In addition, a strong negative correlation between prefrontal cortex and right amygdala activity was found only in subjects with high levels of mindfulness. The ability of the prefrontal cortex to regulate emotional centers and the amygdala in particular has been intensively studied for a long time. And this particular research suggests that the mechanism by which mindfulness enables better coping with challenging situations that evoke negative emotions lies precisely in the enhanced ability of the prefrontal cortex to regulate emotional centres.

All of the previous results were found using magnetic resonance imaging. A team led by Antoine Lutz (Lutz et al. 2004) found interesting EEG changes in the aforementioned group of long-term meditating Tibetan monks during undifferentiated compassion meditation. Compared to the control group, the meditators emitted a significantly higher intensity of oscillations in the gamma band during meditation, as well as a higher phase synchronization between distant parts of the brain (which, from a neuroscientific point of view, is very remarkably reminiscent of the psychedelic experience). Furthermore, in the so-called rest phase, before the start of meditation, the meditators showed a higher ratio of gamma-band oscillations (25 – 42 Hz) compared to lower frequency oscillations (4 – 13 Hz) compared to the control group, and this ratio increased significantly after the start of the meditation and remained higher than before and after the meditation. This research was the first to suggest that meditation practice engages temporal integrative mechanisms and allows for both short- and long-term neuronal changes.

Studies (Slagter et al., 2007) have also demonstrated an increased ability of meditators to discriminate between two auditory stimuli in rapid sequence after three months of meditation abstinence. This experiment also showed that the most successful ones had the lowest brain activity, according to EEG, when the second stimulus appeared. This is interpreted as a sustained ability of meditators to not pay attention to “unnecessary” stimuli, thus increasing just attention capacity.

One possible mechanism by which meditation transforms experience is by distinguishing between self-awareness in the present moment and a kind of personal self-awareness in relation to the past and the future (these are mainly enduring qualities, e.g. what are my physical qualities, what are my abilities, etc.). For example, a study (Farb et al., 2007) showed that meditators activate distinct areas of the cerebral cortex when experiencing present-moment self-awareness and personal self-awareness, whereas for non-meditators these areas overlap. This is interpreted as an increased ability of meditators to distinguish the two forms of self-awareness from each other. And this is the aforementioned felt “space” between the observed and the experienced, which is created precisely by the integration of meditation into ordinary life.

For the sake of completeness, let me also mention here the work of James H. Austin (Austin, 1998, 2006), who is based on Zen practice and attempts to synthesize the existing knowledge into a broader, yet still rather speculative, framework. According to Austin, changes in the thalamus contribute to the suppression of the narrative self and further create the conditions for states of extreme mindfulness (also called kensho or satori in the language of esotericists). James H. Austin, from my point of view, was precisely trying to distinguish between the Old Brain and the New Brain, and thus between the HOS man and the HNE man.

Technology as the future of meditation techniques?

In the introduction to this blog, I mentioned that there are different types of meditation, such as mindfulness or gratitude, that try to direct our brain’s attention and create a kind of “auxiliary intention” in our brain.

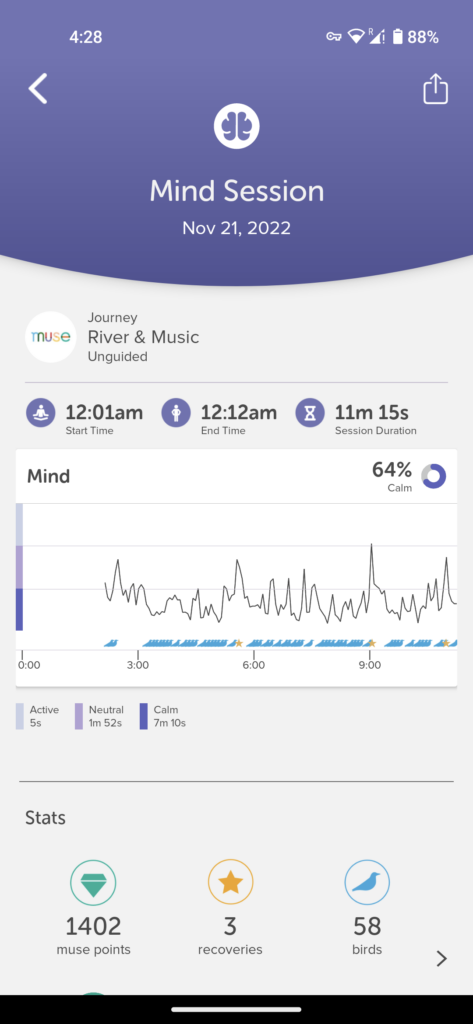

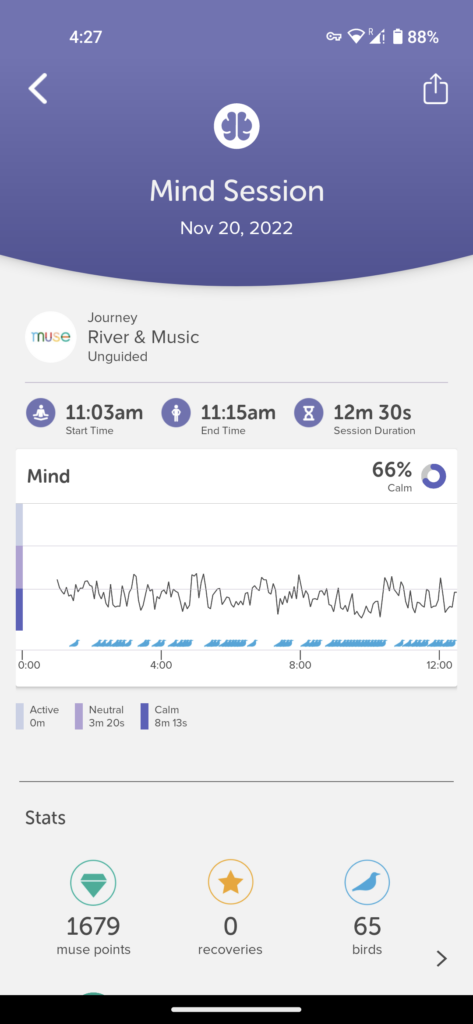

An interesting innovation in the field of meditation from my perspective is neurofeedback; specifically the Muse device. This is a headband containing an EEG that accelerates the learning of meditation not through some auxiliary intention but through adding a new sense.

So how does it work?

The Muse headband measures the “state” of my mind and gives me feedback in the form of sound interpreted by the Muse app. If I get lost in thought (intention), i.e. if I fall off Osho’s tightrope, I hear a thunderstorm and lightning (but I can set the specific sound in the Muse app), I become aware of it and return to the idle state again.

We can experience many such moments of “disturbance” during meditation, but the main thing is that we always improve. It’s funny, because in doing so we may not even know exactly how feedback works. When we get lost in our thoughts we just “quiet the storm”, and when we are absolutely calm and idle during meditation, we “hear the birds”. And even more interesting is that after some time of training with the Muse device, we don’t even have to wear a headband. In short, our brain gets used to the new sense and grows a sensitivity to it (I talked about practically the same thing in my blog about Oura and perception hacking). If we get lost in thought, we can effectively come back because we’ve practiced it every day.

The truth is that our surroundings very often brainwash us with nonsense like “technology is damaging our brains” (or “drugs are damaging our brains”). But it is not that simple. Whatever is around us is just a tool, whether it is technology or drugs, and the harmfulness or usefulness of a tool depends on how we use it. If someone masturbates all day over pornography, argues in Facebook comments, or browses through spyware TikToks of plastic influencers, it’s probably not going to do their brain any good -– just as it’s not going to do their brain any good if its bearer of the tool takes psychedelics every day at a party among dozens of strangers, snorting cocaine in the process. But each of us will suffer the consequences of the way we use the tools.

Muse is therefore not the only way to master the art of meditation and upgrading the mind. Just as different techniques suit each of us, different tools suit each of us. Personally, I find Muse to be a remarkable invention that has certainly found a place in my life, as it expands my consciousness by adding new sense and therefore improves my ability to learn.

Among other things, the new generation of Muse supports other features besides hacking meditation, such as measuring sleep, or putting oneself to sleep through the sounds of neurofeedback app 🙂

Conclusion

Although neuroscientific research on meditation is still in its infancy, we can already appreciate its importance to some extent. First and foremost, it contributes to a better understanding of the neural basis of attention and emotion management. We are also exploring the extent to which neuroplasticity of the brain enables the systematic development of these complex skills. These results then form the empirical basis for explaining the neural mechanisms that are part of psychotherapeutic methods using elements of meditation practice, which include, for example, psychedelic or transpersonal clinics, which we can already encounter in the Czech Republic.

And of course, the benefits of meditation practice are not tied to any spiritual practices or esoterisms. Therefore, neuroscientific or therapeutic evidence of the potency of meditation, as well as various technologies, could contribute to further expanding and enhancing the effectiveness of meditation practice in our culture.