I love the universe ( = reality) and consider myself to be a recursion of it — I am made up of the particles of the universe, whose cooperation allows me to perceive the universe as a totality. Or more precisely, to perceive myself and the relationships I create together with the universe.

How (and why) to hack your perception of the universe?

For me, perception is the absolute basis of self-knowledge; that is, knowledge of reality as it is. So from this statement we could deduce that the more senses I have, the better I perceive and therefore the better I know reality. Well yes, but actually no.

Perception, in my opinion, is not something that is limited solely to our sense organs. It’s an abstract concept referring to very complex processes taking place in our nervous systems. It is the mutual analysis and evaluation of relationships in the brain, which is why I do not distinguish between perception and thought; in all cases it is merely the activity of the nervous system. However, the only thing that is important in terms of my existence is the output of this whole complex neural process, i.e., what action I perform. I will clearly perceive the guy with the knife rushing at me with my visual sense, while I will evaluate in my brain that I am not in danger and I will stand still. In this case, perception has failed and the resulting output is very messed.

I may disagree with the majority of the population in my view of perception. In fact, the majority population doesn’t give much thought to perception at all.

The point, in short, is that that majority population tends to regard its subjective experience as an interpretation of objective reality (and in extreme cases, not just in terms of reality being captured by some sensory organ, but also in terms of its subsequent evaluation by arbitrary brain activity).

I find the experience of such people very strange. Individuals of the human species in such a state are often unaware of what form their subjective experience is actually made up of, what their fat organ in the cranial cavity is trying to suggest to them, and so ultimately they don’t even know what they want. The resulting output of their cerebral activity is mostly very messed. At least from my point of view, anyway.

It is very important for me to have my perception “hacked” for cognition of reality, and to understand the signals my senses are trying to convey to me, in order to avoid messed outputs (and to avoid ending up like the members of the majority population mentioned above). That’s why I do meditation, yoga, biohacking, or any other sensory expansion that allows me to hone my perception.

What’s more, I can practically test my perception. If I have it well-hacked, I just feel good because I can respond beautifully and cleanly to the stimuli my body is giving me, and I am confident that I somehow understand it. It is a beautiful and pure feeling, which I would describe in layman’s terms as “the realization that I am a collaboration of multiple structures instead of identifying with one structure”.

For me, perception is basically a kind of epiphenomenon of intelligence. It’s about keeping track of my goal and constantly checking against each other the effectiveness of the algorithms that get me to that goal. I would venture to say that perception without intelligence (and vice versa) doesn’t work very well.

Some animal species are able to respond effectively to complex environmental cues, and use them to their advantage to achieve their goal. Humans are the most effective of all organisms at doing this. As technology has developed, humans have specified the use of their knowledge, behaviors, and called this set of activities intelligence. Most importantly, we can change and expand our intelligence with different tools and change our perceptions along with them.

And having used the language of the layman, I would venture to use the language of the esotericist. Indeed, poor intelligence and its impact on perception has been described by Mr. Jiddu Krishnamurti, who has argued that separation is the basis of all conflict. I would like to add to it a little (so that non-esotericists also understand it) — separation is the basis of every psychological conflict. If I identify with any particular structure in my brain, conflict will automatically arise in me. And this is simply because my brain is made up of other structures as well. However, if my brain becomes aware of structural cooperation, it gets into what Mr. Krishnamurti called “the analyzer is the analyzed“.

(Poor intelligence arises precisely when its algorithms have different goals and fight among themselves for their own dominance. In practice, then, it looks like the intelligence has trouble making decisions, and this conflict manifests itself in all sorts of unpleasant psychological states in our, human, perception.)

I myself, for example, claim that a person has only two choices during his lifetime — he can either hallucinate or pseudo-hallucinate. If he pseudohallucinates, he has a starved perception and he gets into the very state described by Mr. Krishnamurti.

Cyborgism, Oura ring and new possibilities of perception

People often want to have many instructions for their lives and therefore tend to question whether they should try meditation, the Oura ring, yoga, sports, and XY other things. If someone asks me about something like this, I can give them some advice in the form of subjective experience with this or that thing the person asks me about, but the only correct advice is “If you have a hacked perception, try it and see if it does you any good. And if you don’t have it hacked, then hack it!”

There is a separate term for hacking the senses, e.g. “cyborgism”. More specifically, cyborgism is about adding new senses through technology. However, this concept is also just an abstraction — our brains respond by adapting to our environment; whether we label some part of the environment as technology or not. Each of us is more or less a cyborg.

I bought Oura in order to move on. To hack my body and mind, that is, to improve my ability to perceive. To have access to the signals that Oura’s hardware relays to my software, which I pick up with my visual sense from my smartphone screen and evaluate in my brain.

For me personally, Oura is a beautiful and effective simplification of life. I learn from Oura algorithms, they are easy enough for me to understand, and if I follow them, I do well. If you feel that you don’t want to go through this learning process, just don’t buy Oura.

How the Oura sensors measure?

The Oura ring has three sensors:

- Infrared photoplethysmographic sensors (PPG) to measure heart rate and respiration

- Negative temperature coefficient (NTC) to measure body temperature

- 3D accelerometer to measure movement

PPG

The PPG sensors are similar to those found in some hospital settings that use them to monitor heart rate. The PPG in the ring emits light through LEDs and receives it through a photodiode that picks up how pulses of light passing through the arteries reflect the activity of my heart.

Oura samples 250 times per second and claims itself to be 99.9% reliable compared to an electrocardiograph (ECG).

The PPG system at Oura is designed to maximize data quality by taking advantage of sensor placement and infrared light. The placement of LEDs on either side of the finger allows Oura to always measure the clearest signal, unlike such Apple Watch that have a one-sided light source.

Oura’s infrared light penetrates deeper than the green light used in most wearable devices. However, it is sensitive to motion. For example, the 2nd-generation Oura only took your pulse when you were asleep or if you activated the Moment function during the day.

The third generation, which I use, measures heart rate nonstop, but is still sensitive to some movement. For example, when I’m running, it occasionally misses.

NTC

Oura monitors skin temperature using an NTC temperature sensor that can detect changes as low as 0.1°C, making it one of the few wearable devices that measures temperature directly on the skin rather than estimating it from the environment.

Temperature informs a lot of information about my body, such as how my body is recovering, if illness is approaching, or how hormones are working in my body. Or whether I’ve remembered to turn off the heating for the night :))

Oura displays body temperature relative to my baseline temperature instead of comparing it to absolute body temperature. For example, instead of showing my temperature as 36.5 °C, Oura will show how much higher or lower my temperature is than my baseline temperature (+0.1 °C). For example, I know that my baseline is naturally lower than most people’s average.

3D accelerometer

3D accelerometer captures activity during the day, restlessness at night and therefore helps with determining sleep phases. If I’m restless and tossing and turning a lot at night, then Oura gives me red numbers in the “Restfulness” section in the morning.

During the day, the Oura automatically captures most of my daily activities and workouts (for me, it’s mostly walking and yoga; I practice those multiple times a day). The ring provides updates on activity progress and reminds me to get up and move after long periods of inactivity. If I don’t move for more than an hour a day, it throws an “Alert” and notifies me with a notification.

As a fan of permanent flight mode, however, I don’t encounter notifications. After all, I don’t even need them, as I move around enough (even during my 4-hour train journeys between Bratislava and Prague).

Updates and Brave New Oura

Oxidation and breathing regularity (october 2022 update)

The Oura update offers a Blood Oxygen Sensing (SpO2) feature for its members, providing insights on Average Blood Oxygen and Breathing Regularity during sleep. Average Blood Oxygen measures the percentage of oxygen in blood, while Breathing Regularity detects unusual breathing patterns. Healthy blood oxygen levels range between 95% and 100%. Low oxygen levels can indicate potential health issues.

Common causes of low blood oxygen levels include lack of environmental oxygen, lung diseases such as asthma, sleep apnea, heart disease, certain medications, and alcohol use. Oura Ring Gen3 measures SpO2 using red and infrared LED sensors. Oxygenated blood reflects more red light, while poorly oxygenated blood reflects more infrared light. Measurements are taken during sleep periods longer than three hours. The data provided by the Oura Ring is not meant for diagnosis but to share with healthcare providers for informed discussions.

Body clock, chronotype and improved sleep stage tracking (march 2023 update)

Both Body Clock and Chronotype features are available for Gen2 and Gen3 members with active membership.

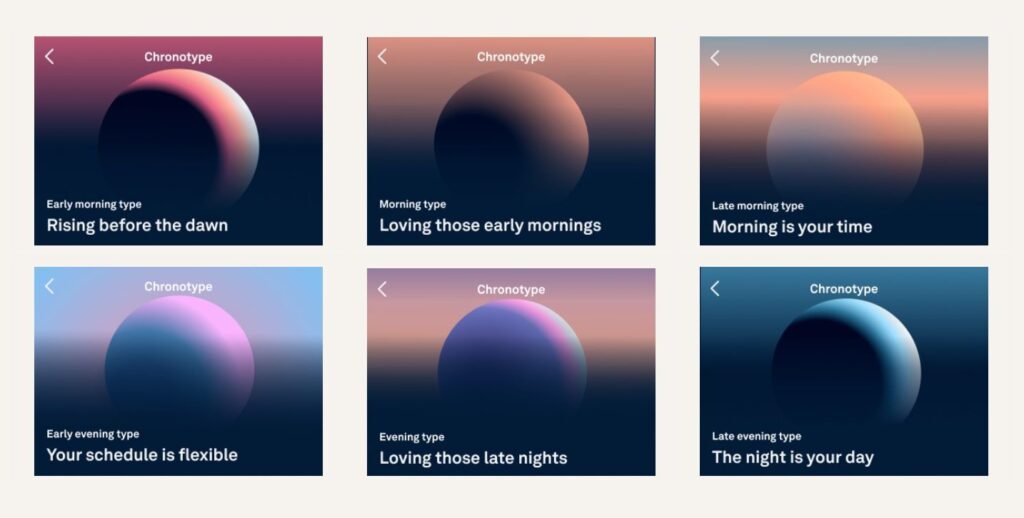

Chronotype indicates whether you are a morning person, night person, or somewhere in between. Oura classifies chronotypes into six types: early morning, morning, late morning, early evening, evening, and late evening. To calculate your chronotype, Oura uses data from the past 90 days, looking for at least 30 periods of long sleep (more than three hours), and analyzes activity, body temperature, and sleep patterns during that time. Note that naps are not included in chronotype calculations.

With the new Oura update in March 2023 also came improvements to sleep detection algorithms. On the Qunatified Scientist channel, the author did a comparison of Oura with a reference EEG headset and concluded that the new Oura algorithm is comparable to the best non-EEG sleep tracker – the Apple Watch.

In August 2023, Oura brought another update that allows you to share your “readiness” score with family and friends. Something like this comes in very handy if, for example, you’re planning an activity together and want to be clear on whether others are in the same “mode” as you; whether you want to go hiking or just chill at home in front of the TV.

Another new feature is the average impact of “tags”. For example, you add the tag “morning sunlight”, meaning you were exposed to sunlight in the morning. You’ll learn that when people added this tag, they then had 2% higher heart rate variability overnight. Or people who added the tag “alcohol” have a correspondingly 11 points lower HRV.

What are the main lessons that Oura gave me?

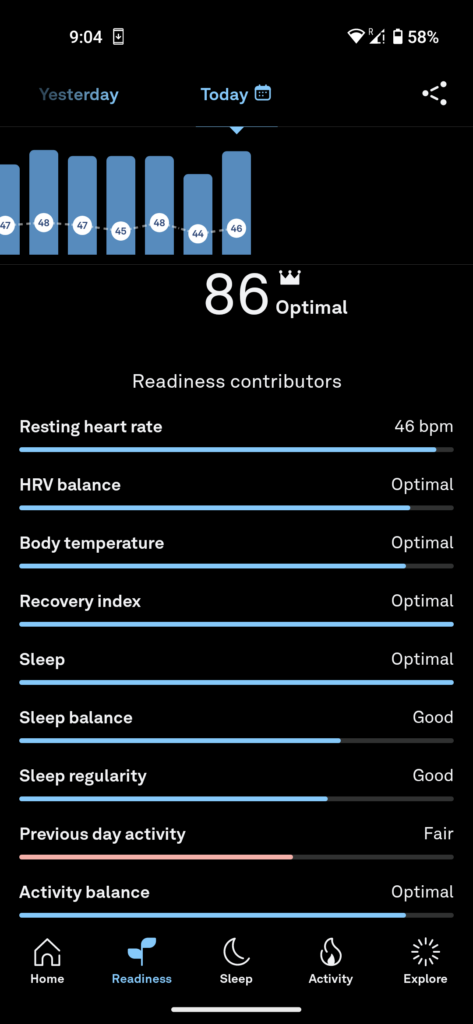

I put on the Oura Ring 3 on November 24, 2021. In that time it has calibrated a bit and I have learned how to work with it. Thanks to the numbers from the algorithms, I can feel my body much better. Today, for example, I got up and told myself that it felt like Readiness-in-range 85-95 and Sleep-in-range 75-85 and I guessed right. And I guess right almost every time.

But the fact that I “guessed the numbers right” doesn’t necessarily mean anything. In practice, though, it’s that I’ve become much more sensitive and can better recognize when my body is ready (and especially for what kind of activity/inactivity).

The first important redpill from Oura for me was definitely sleep. Even the father of biohacking, Dave Asprey, has talked about sleep being the greatest biohack of modern times.

But for example, it’s one thing if you theoretically know that eating less than 4 hours before bedtime will disrupt your sleep quality, and it’s another thing if you measure it and your brain develops a sensitivity to it.

And of course, sleep isn’t just about eating. As I continue to educate myself on my body, I’m also discovering what bedtime activities work for me, and which ones don’t. I know, for example, that if I’m up late into the night studying something or writing a text, it will affect the quality of my sleep. However, I can hack this very easily by putting theta waves (4-7 Hz) into my headphones just before going to bed and warming up my cerebellum with an infralamp for 15 minutes.

Sometimes I also find it helpful to support my glymphatic system with a spoonful of homemade honey before bed. However, there are some variables here too — if I have a quick glucose fix after I’ve consumed some extra fatty food, it’s more likely to harm my sleep than help it.

And it’s the variables that bring me to another important Oura redpill, which is just volatility.

Oura has brought a lot of (beneficial) volatility into my life through the realization of how much of a variable and dynamic mass my (human) body is.

Our ape ancestors didn’t get up regularly every morning to hit the gym and eat regularly. Periods of hunger were replaced by periods of food abundance, periods of great physical exertion and activity were replaced by periods of rest. And that’s exactly how I do it; depending on what the outputs of my Oura algorithms (= mostly, therefore, my own feelings) are compatible with.

Many people avoid volatility and bring regularity into their lives. I won’t address the psychological analysis of why they do so here. But they do. Whether it’s regularity in the ritual of an every-Friday booze binge with friends, or in the ritual of a daily workout at the gym. They may be completely different rituals, but the principle is still the same.

It’s like the difference between customers of a “normal” bar and a gaybar. In both types of bars we can meet different communities of people with different preferences, but their goal is the same — to soak up the atmosphere of noisy pop music and alcohol and, in the best case, to find a sexual (or even life) partner who likes to spend his free time soaking up the atmosphere of noisy pop music and alcohol.

As is the case with the customers of bars and the customers of gaybars, the intention of the proponents of the rituals of regularity has the same psychological basis. Thus, whether one is an advocate of the ritual of the regular Friday night booze binge or the ritual of regular exercise, one does the ritual in order to receive a reward in the form of a specific feeling from one particular brain structure for having satisfied it and fulfilled its specific need (or at least what the analyzer, who was unaware that he was analysed, considered to be the need). Something similar happens in the brain of a person afflicted with OCD.

So, the conclusion I would like to punctuate my entire blog with is this: don’t avoid volatility. Volatility is not just around us. Volatility is within us!