I. PHILOSOPHICAL PART

A little reflection of blind idiot monkeys on a blind idiot god

If you don’t know what memes and memetics are, don’t worry. You will learn everything in this article. But first, I would like to reflect on the civilisationally very popular concept of free will, which is undoubtedly related to memes and memetics. And of course, as a fan of Howard Phillips Lovecraft’s literature, I leave you with the character of Azathoth, a.k.a. the “blind idiot god” from the poetry collection Fungi from Yuggoth, as a tool for reflection.

Azatoth is referred to in Lovecraft’s mythology as the “blind idiot god” for good reason. He is a god who creates our reality by dreaming it. And of course, some deities from other dimensions have fetishized his dreaming to the point of keeping our beloved Azatoth asleep, because if Azatoth were to wake up, reality would dissolve. And as we can all see, Azatoth must really be a god, because he is an extreme chaos maker. His dreaming brain has produced all the shit of the known universe, including us.

And why did I choose Azatoth as a tool for reflection? Of course, the only correct answer is that memes are to blame, and Azatoth is a meme that got into me. But still, I think it’s a very useful meme because it helps us visualize how memes actually work.

I would venture to say that based on the existence of memes, we humans are even more idiotic and blind than Azatoth. And not because we are the product of Azatoth’s creative mind 🙂

We are more idiotic and blinder because our dreams, unlike Azatoth’s, are not the product of our minds. Our dreams are the product of memes, or more accurately, the byproduct of memes. And we are the ones who dream the dreams of those who keep us asleep. That is to say, we are those who dream the dreams of memes.

Debate on free will

I have noticed that if I talk to someone not directly about Azathoth, but about the illusion of free will of the monkey species Homo sapiens sapiens, people who are familiar not only with Fungi from Yuggoth, but also with Dawkins, Hofstadter, or terms like ”meme” or ”memetics”, usually immediately agree with me and don’t even want to discuss the possibility of free will. And on the other hand, people who don’t have similar knowledge are usually eager to argue and happy to debate.

Based on the data I’ve gathered from interacting with other people, I consider knowledge of the principles of memetics and memes to be a very key phenomenon in a person’s life. After all, memetics, as a branch of biology, explains to us in pretty simple human (memetic!) language what the fuck is going on (!) and why people do what they do.

Me != My DNA

And if I ever feel like spending my time discussing and debunking the illusion of free will in the Homo sapiens sapiens ape species, my conversation usually consists of two disciplines, starting with DNA and ending with memes.

Most people then tell me that my will is determined by my “I”. And what I am, after all, are cells with my DNA, or something like that.

But that’s far from true (well, memes don’t tell much to a person who hasn’t shifted in their perception of the world from the DNA level perception of their “self”).

For every cell with human DNA in our body, there are 10 cells with different DNA. And they’re bacteria.

Many of them live in symbiosis with us and form an integral part of our digestive system. We are constantly exerting all kinds of energy to feed them. And they don’t have to do anything but wait patiently for food and reproduce. That’s also why their DNA has been evolutionarily simplified to the minimum necessary — bacteria are actually very tiny and don’t need to do many of the activities that quanta of their relatives outside our bodies have to do.

Bacteria are undoubtedly a part of us. After all, they too send protein signals to the same body in the same way that cells with human DNA do. They co-create our perception.

And then what about the bacteria that directly influence the brain’s behavior? A beautiful example is the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii — a parasite of the cat that spends part of its life in the blood of warm-blooded animals such as mice. It is capable of generating neurotransmitters that direct the behaviour of its host so that it does not experience fear and behaves in a risky way. In the case of mice, for example, it makes them easier prey for cats, a target destination for toxoplasma. The same is true for humans, although they are usually not eaten by cats, but become lifelong carriers of toxoplasma. Humans who are infected with toxoplasma have slowed reactions. They suddenly perceive everything differently because toxoplasma has become part of their consciousness.

No one knows how many such bacteria are part of our bodies. But what is certain is that they are involved in the perception of our “self”. I don’t even need to talk about viruses, which are in our bodies in far greater numbers than bacteria.

And this is precisely the point at which the conversation about free will moves from the discipline of DNA to the discipline of memes. An opinionated opponent in such a situation will usually argue that subjective human experience is absolutely unique. That some viruses and bacteria may indeed bend it in all sorts of ways, but not create a kind of “core” to the organism. And by this “core” do opponents usually mean nothing more than that my feelings, preferences, thoughts, and opinions are, for the most part, my own after all. Or not?

Really not. It is our beloved discipline of biology — memeology, or more accurately, memetics — that can give us the truth.

According to memetics, our “self” is merely the output of memes in a competition to acquire as many individuals as possible. Each of us is part of a culture made up of the selfish interests of memes, and this is true whether you are in bed, at the bar, at the theater, or writing this blog right now. Since birth, the human neocortex has been sucking memes into ever more complex and intricate structures, and individuals affected by them have become an integral part of history, tradition, religions, technological development, fashion, gastronomy, political organizations, and lifestyles.

And from old memes new memes are formed. We do not choose them, but they choose us.

II. PRACTICAL PART

What exactly are our lovely memes?

We’ve already learned some abstraction about what Azatoth is, what memes probably do, and that they use human vectors to spread. But how can we imagine such a process in everyday life?

That is what the Practical part of this article is for, when we put memes and memetics into practice and learn about the process of their creation as well as what tools memes use for their replication. So you can sit back and analyse with me about memes as the source of what we call our “consciousness” or our “self”.

Whether one has ever heard of memes or not, the fact of human culture is a constant source of wonder to oneself. Where and why did all those offices, hospitals, automobiles, books, theories, works of art, science, technology, politics, economics, and all that we consider “human” come from? Where and why did the money come from? What could such a monkey possibly use it for?

As has been said before, as in living or non-living nature, in this nature of theorizing monkeys in cars and offices, we will look for replicas of some patterns, and also for replicators within which the replicas are replicated. All elements of civilization, or culture, exist only within the social interactions of us monkeys (sapients).

A poem or an atomic bomb — if it were not for the sapient who responds to the poem or the atomic, neither the poem nor the atomic bomb would be distinguishable from such a watercourse or a forest, because no one would be able to distinguish whether it was a bomb, a watercourse, a poem, or a forest.

There are artifacts created by sapients, we just don’t know their contents anymore and are constantly trying to “discover” them. This applies, for example, to all the prehistoric artifacts that are cave paintings or Stonehenge. Actually, we only know one thing for sure of their meaning to the sapient — they were created by the sapient, they were not created in any other way. And from this it can be clearly seen that the artifacts have their content not in themselves but in us, the sapients, that they are only certain patterns that are replicated from one sapient to another. In the prehistoric ones, part of the patterning has been lost, which was probably replicated orally, and therefore we no longer know the whole pattern of that information, but only part of it (the painting, the shape of the stone).

From the above examples it is clear that we can call any social interaction between some organisms living in societies a social replica.

This fact was pointed out in 1976 by Richard Dawkins in his book The Selfish Gene. His motivation was to point out the informational nature of the gene, which is understood here as a piece of information that reproduces itself — replicates itself. To give another example of such self-replicating information, he introduced the notion of a cultural gene, which he called a meme (which is actually a corruption of the Greek mimema (to imitate)).

But in doing so, Dawkins introduced a neo-Darwinian evolutionary idea into theories of human culture and its development.

Our every thought. Our every word is a meme (or more accurately a memebiont, but we’ll talk more about those in the next chapter). Every single element of sapient culture that we can separate from other similar elements is a meme. For example, every letter of every word. Every single item of clothing, note of a piece of music, the clink of champagne glasses, or brushstroke on a canvas. Every single part of a machine, every single work action. All of this can be considered a meme.

All of these replicas – memes – are replicated in the sapient population in the same way that eye colour, head shape, the way a sexual partner is chosen, or the reaction to danger is replicated. They are similarly, or even equally, subject to the selection pressure of natural selection. Those replicates that can spread faster among sapients, or satisfy more of the sapients’ needs, spread at the expense of those that can do so less well.

And we will discuss the actual mechanism of replication in the next chapter.

Replication as materiality in the abstraction of memetics

To get an idea of meme replication, let’s first consider a particular instance of a meme. For example, such a dog Kabosu (that’s the dog known from the DOGE meme).

Kabosu the dog has a double life. He lives as a dog and he lives as a meme, and both of his lives can be considered fully organic. While his dog life is palpable (at least it is for those who have had the privilege of getting close to the physical body of this most legendary living master of internet memes in the world), the memetic life (i.e., replication, metabolism, and intentionality) is undeniably localized in our brains.

And this is exactly what memetics is about. Memetics assumes the action of natural selection on cultural elements (memes); it tacitly assumes the source of intentionality in the human mind, but without explaining what that mind actually is. Moreover, something about all this doesn’t sit right with me. There smacks of some internal inconsistency here.

What does natural selection work for in an organic world? On the patterns of organisms, patterns which are the expression of the intentionality of the living creature, patterns by which they expose their intentionality to the selective pressure of the environment. Just what sign for the intentionality of a sapient can be not only the dog of Kabosu, but also, for example, such a shovel, or an AI? The mind, consciousness, or “I” (whatever that is) has evolved to fulfill other purposes, after all. Or did it not?

It really didn’t. The real memeological paradigm reversal is in the acceptance of the intentionality of such reaction structures in the brain whose features have some relation to the Kabosu dog, the shovel, or AI. Memetics allows such structures full organicity, treating them as living entities with all that goes with it. The human mind, on this basis, is something like an ecosystem of these living beings, competing for resources and working together in symbioses. Just as in the organic world. They also reproduce in variations, and this is the subject of Darwinian natural selection. The Sapient is then really just a monkey whose brain is the substrate of this evolutionary panopticon. I believe this very concept will also help to better describe the AI phenomenon.

So if Kabosu, the shovel, or the AI in the brain is a meme(biont), a living being, then what is Kabosu as a dog and what is their relationship to each other? To understand this, we must first say what is the brain, what is its purpose in an organism. The purpose of the brain in an organism is no different than any other unit or organ of any organism — to reproduce itself and to accumulate resources in the environment for that purpose. Interaction with the environment marks reactivity to its elements. Something is taken from the environment, and something returns to the environment in response. Organisms act on the environment, making changes in it.

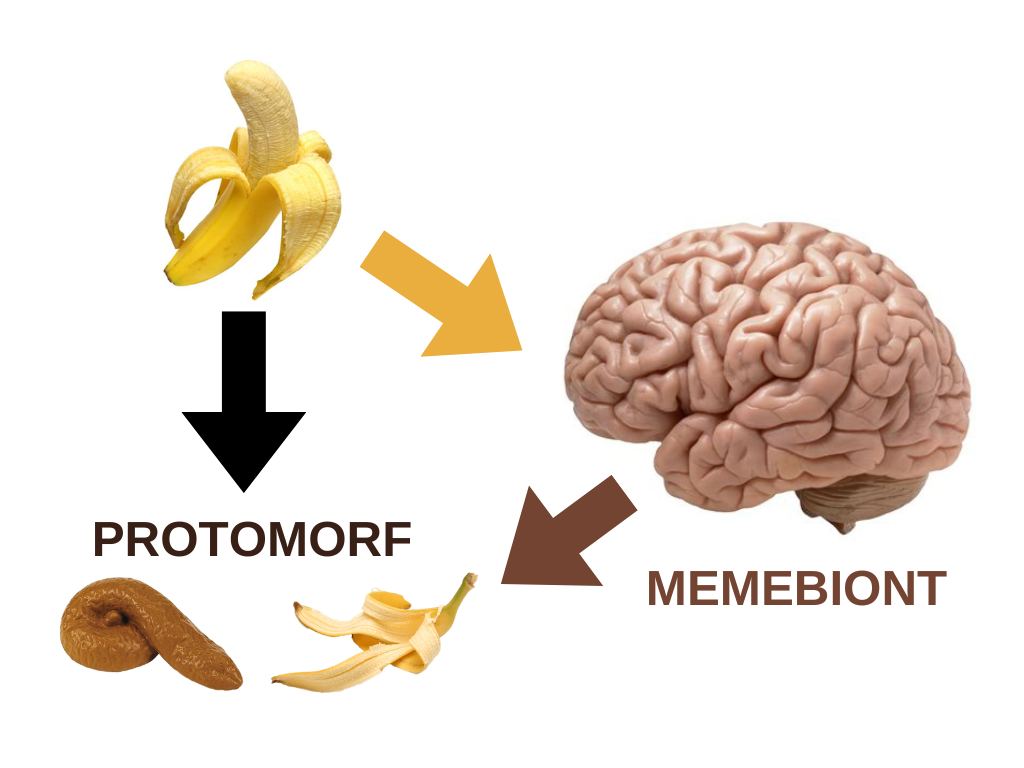

We see this situation in the example in the following figure. On the left is the environment and on the right is the brain of an organism. The banana in the environment has a reaction structure in the brain, which I call a memebiont, that recognizes an element in the environment, evaluates its importance to the organism as a food source, then activates muscular coordination to grasp the banana, peel it, insert it into the digestive tube, ingest it, activate digestion, etc. The consequence is a change of environment, which (a memetics-obsessed comrade of mine performing under the pseudonym Daimonion von Cave) called a “protomorf”. If a whole banana was part of the environment, the organism’s action turned it into banana peel and excrement.

From this perspective, organisms change the environment into protomorfs by their action on the environment. And protomorfs can become a necessary resource for the needs of other organisms, which transform them into other protomorfs. It is important to note, however, that if an element of the environment that was of importance to an organism has been converted into a protomorf, it has automatically lost its importance to that organism.

And this is how things have been happening for billions of years. But it was only a matter of time and a few evolutionary steps to evolve a different process, one in which a change in the environment does not lose meaning for the generator of that change, and indeed that change in the environment changes the reaction structures of other brains of the same species in its pattern, that is, it generates the same meaning in them. This situation can be seen in the second figure.

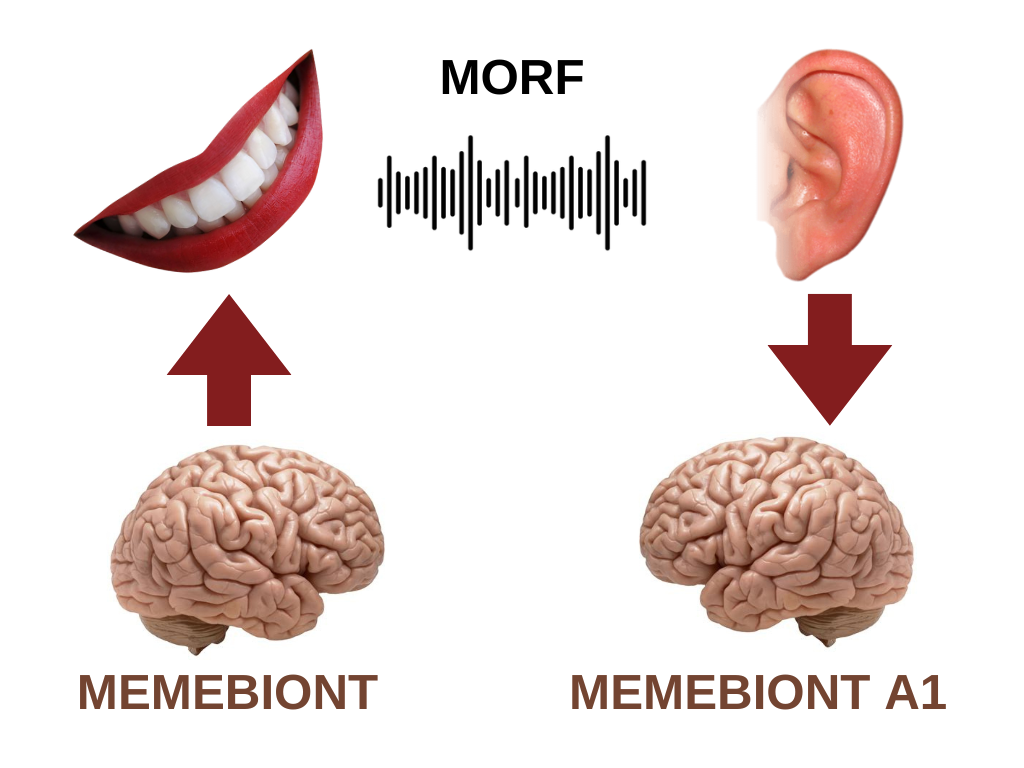

Memebiont A in the left brain is the reaction structure of an acoustic signal, for example, a word. This structure consists of the phonemic structure of the acoustic signal from the auditory receptor and the muscular cooperation of the vocal cords and respiratory muscles needed to repeat the sound. Memebiont A causes the sound waves to change the structure of the environment. This change in the environment subsequently causes another brain (if it was not there before) to form a similar or identical memebiont A1 to the brain that caused the change in the environment. Such a change in the environment, which has this ability, was in turn called a “morf” (from the Greek morphí (shape)) by my friend Daimonion.

A morph is such a change in the environment that stores in its structure the code to create memebionts in other brains. Since a memebiont is an immaterial structure of synaptic connections between neurons, the only way it can get from one brain’s environment to another environment is by some materialization of it.

The more attentive reader will surely recognize a parallel to the organic world here. An organism is also essentially an immaterial “organization” of material shapes, or molecules. This organization cannot be transferred to other individuals except by encoded materialization, formation and morphing into some material structure. And that is DNA. Morphs are to the memebiont world what DNA is to the molecular world. But this is where the similarity between morphs and DNA ends, because as far as I know, no molecular organism passes its DNA out of the cell, that is, out of the living environment, in order to create a new organism in a different environment. It is only partly reminiscent of viruses.

Speech, Kabosu, the shovel, AI, buildings, writing, texts, the internet, in short everything that constitutes the “palpable” elements of culture, are morfs. The actual structure of the memebionts in their brains is not in them, but only the code to create them. This code is read and interpreted by other memebionts in the brain, and these participating memebionts strive for their own survival in as many copies as possible. In the brain, this means that pre-existing reaction structures form new reaction bonds based on the interpretation of morfs. For example, if a word (a phonic memebiont) already exists in the brain, it is activated in the morf of a sentence and combines with other word memebionts that are activated from the same morf to form a memebiont of that sentence in the brain.

From the perspective of this whole non-small article, it is important to note that morphs are a consequence of the intentionality of memebionts in brains. Memebionts want to reproduce, they need to survive their extinction in brains, and morphs are their means to that end, much like the means of survival of organic creatures is their DNA. To put it in Darwinian terms — those memebionts that are able to produce morfs are selected by natural selection and survive in their offspring, while those that cannot perish with their brains.

The peculiarity that the replication code is outside the body that interprets it brings a fundamental difference between meme and molecular life, and brings new insight into, for example, the topic of AI. But I’ll write something about that again some other time.

Memes, memes, memes

And what to say in conclusion?

Well, the interesting thing about all of this is that memes as replicas of social interaction are, in my opinion, inherent not just to us Homo sapiens monkeys, but to every socially organized organism. Social insects like bees or ants pass on memes about the environment they are in. Flocks of birds, or herds of ungulates, or troops of monkeys (not just us), schools of fish — these are all examples of organized organisms, where the very word “organized” indicates the way in which these groupings must transmit replicas of states of the environment, states of themselves, or states of the whole.