DISCLAIMER: This article is for educational purposes only.

We are currently (2022) experiencing a small psychedelic renaissance again after the 1960s, and I would venture to say that the perception of psychedelics in our society has changed since then, as has the perception of meditation – it’s no longer just hippies in flip-flops meditating (and tripping). The topic of psychedelics is being addressed positively by more and more scientific and psychiatric experts, we are hearing more and more about how someone discovered the magic of microdosing (LSD is used by Silicon Valley scientists, for example, to increase productivity), and we even have ketamine and psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy in the Czech Republic.

But what inspired me to write this article is neither scientists, nor psychedelic clinics, nor microdosing. It’s primarily my friend Patrick and his brain.

Patrick and his Brain

“Why?” one of my friends, Patrick, asked me.

And the answer to his “Why” will actually be this entire article, but first let’s give the whole story behind his “Why” question.

My friend Patrik is interested in medicine, neuroscience, and everything that somehow relates to it. We got to talking one day and just as we were discussing the issue of neural activity during a psychedelic experience, Patrik brought up quite an interesting topic. He talked about how much he used to “identify” with his name (or more accurately – with the concept of “Patrick”), which is what his acquaintances used to call him in the past. And it didn’t matter whether the acquaintances talked to him privately or gossiped about him behind his back. In short, Patrik always became alert upon hearing the name “Patrik” and felt that things “about Patrik” concerned him immediately.

However, as Patrik underwent several psychedelic trips, something was very different about him. He told me specifically about a situation where he was sitting in a room with his friends and heard them talking about “Patrick having a problem”. At one time, Patrik would have jumped out of his chair and responded immediately, but this time Patrik didn’t feel identified with the “Patrik” his friends were talking about. He didn’t feel that the issue had anything to do with him and therefore didn’t even consider that he, like Patrick, had a problem. He therefore just remained sitting quietly in his seat, wondering who the ‘Patrick’ his friends were talking about actually was.

And Patrick’s “Why?” was about this very issue. Why was he suddenly different than before? Why was he thinking differently and seeing different connections in things?

A Parallel with the Integration of Micro-Idles

If you have already read the last article from the series “XY and the altered reality”, you will already know that Patrick has managed to integrate into his everyday life a kind of “micro-idling”, thanks to which he has freed himself from some of the reaction patterns (intentions) of his Old Brain and has created a kind of “space” between what he observes and what he experiences. Then, instead of identifying with his “I”, Patrick began to merely “observe that he is identifying with his I” (PHASE 1 from the last article) and later he began to observe something other than identification. In this case, he even began to “observe that he does not identify with his self” (PHASE 2 from the last article).

Patrick’s brain has undoubtedly been structurally transformed, but how is such a thing possible when Patrick, as he himself claims, has never meditated? So how exactly does the psychedelic experience affect our brains, in what ways does and in what ways doesn’t it resemble meditation?

How Do Lysergamides Work?

Of course, to understand all the structural changes that can occur in a human brain during (and after) a psychedelic experience, we need to understand the effect of psychedelics. For the case of our article, we will talk about lysergamides, which Patrick, for example, has experience with.

(Lysergamides are by no means limited to illegal psychedelics. We can find among them, for example, 1cP-LSD, which is not covered by Czech and Slovak legislation in any way.)

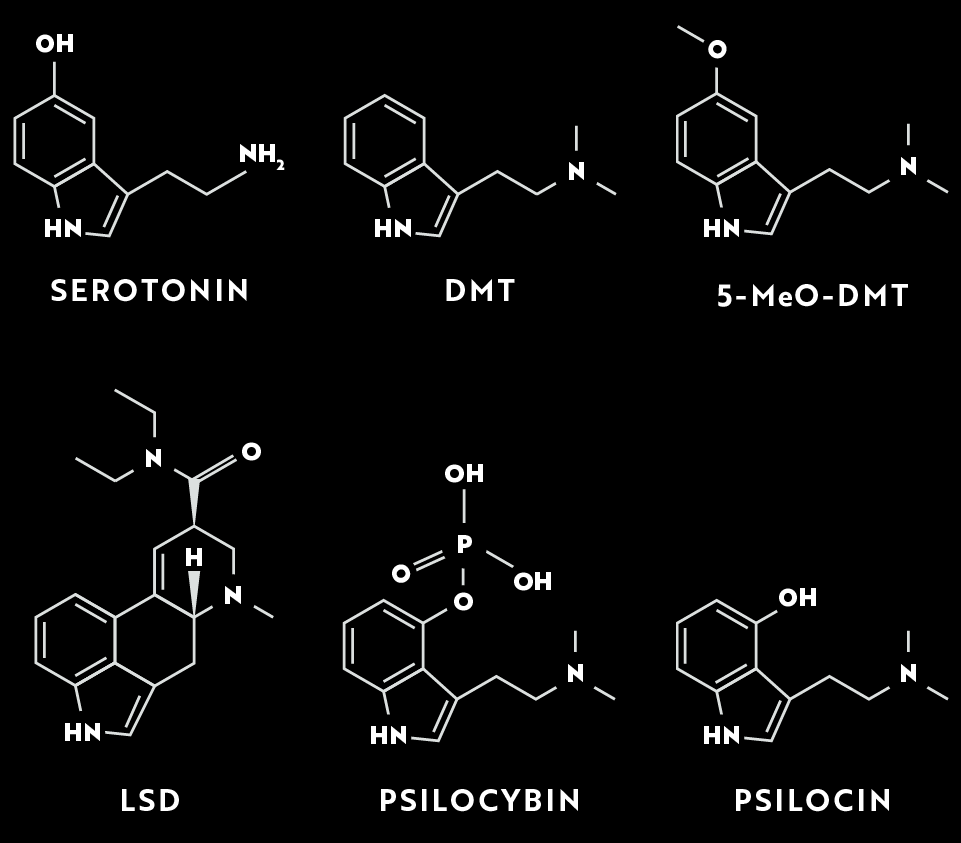

How do lysergamides actually work? Lysergamides, like tryptamines (which include classical psychedelics such as DMT, psilocybin or even serotonin), interact with the serotonergic system in the brain. This means that they bind to serotonin receptors. And they do this simply because they are molecularly very similar to serotonin.

However, while serotonin binds to approximately twelve different subtypes of serotonin receptors, psychedelics bind to a very specific subtype, called the serotonin 2A receptor. 1cP-LSD and other lysergamides bind most strongly to several other subtypes of serotonin and dopamine receptors, but to a lesser extent. But, for the psychedelic experience, the serotonin 2A receptor is the most important.

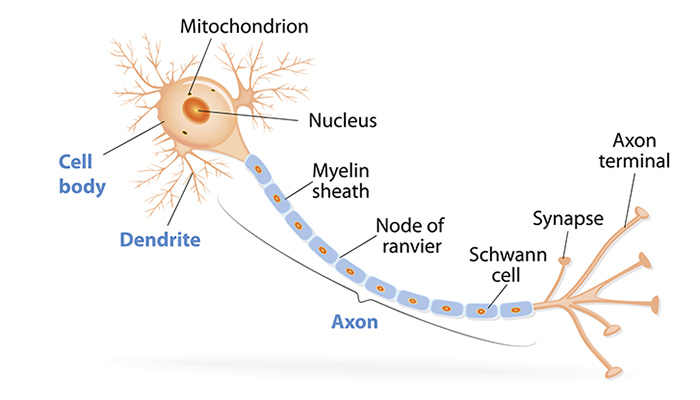

Serotonin 2A receptors are found on a specific type of neuron, which have long axons (bulges – anyone who didn’t pay attention in high school biology should take a look at the picture below) that arc across the entire brain, unlike neurons with short axons, which only connect to cells in close proximity to them. The axons of these long neurons leave the cerebral cortex and extend to areas below the prefrontal cortex. This gives them control over the areas to which they are connected, in this case the areas responsible for emotional and stress responses.

It should not be forgotten that neurons can be either excitatory or inhibitory. An excitatory signal prompts the neuron to “fire” the signal, while an inhibitory signal tells it “not to fire” again. Psychedelics stimulate serotonin 2A receptors, and these are localized precisely on the excitatory neurons that are activated by them. So logically, one would think that ingesting a psychedelic substance would lead to increased (excited) neuronal activity in the brain. Paradoxically, the opposite is true. But how is this possible?

Lysergamides bind to the serotonin 2A receptor and cause the neuron to fire an excitatory signal. When these neurons fire, they also stimulate bystander inhibitory neurons that also have serotonin 2A receptors. So something like a massive shootout between neurons is going on in the brain – massive firing and even more inhibition at the same time. Over time, the inhibitory signal will override the excitatory signal, and this is what leads to a reduction in overall brain activity.

Just because serotonin and psychedelics bind to the same receptor doesn’t necessarily mean they produce the same signal. Scientists, dilettantes of the limitations of their time (like everyone else), have long thought that neurons function like some kind of light switch – they are either on or off. But according to this theory, psychedelics and serotonin would have to have the same effect – either binding to a receptor and activating it, or unbinding from it and deactivating it. Fortunately, we now know that each molecule interacts with the receptor in its own unique way, giving rise to a unique signal within the cell. And why is this so?

It’s just the simple geometry of physical space behind it. When a molecule binds to a receptor, the receptor has to adapt to the molecule by changing its shape. And that activates certain signaling pathways in the neuron. Among nerds, this principle is referred to as so-called “functional selectivity” (just in case you want to look into this further).

Time

Okay, so now we know what receptors psychedelics act on and why they have different effects on human consciousness than molecules that act on these receptors naturally (i.e. serotonin in the case of non-tripping). But what influences, for example, the duration of the effects? A person familiar with the effects of lysergamides will know that a psychedelic trip on LSD and its derivatives can quiet easily last for 12 hours, possibly longer. Why is this so?

Serotonin molecules usually finish their job very quickly. They are released from the receptors within fractions of a second after they bind to them. In contrast, when such LSD binds to a receptor, the receptor collapses over its large molecule, forming a cap that prevents the LSD from unbinding from the receptor. Thus, unlike serotonin, LSD is certainly not some lazy drug – it has just paid the price for its size and shape, and so remained trapped in the receptor for several hours.

While the LSD molecule is trapped in the receptor, it causes the receptor to send signals – for several hours and sometimes longer. This is why LSD users feel the effect with just micrograms of the substance lasting 6 to 15 hours.

Connector Nodes

So we already know that psychedelics don’t affect our brain’s executive functions, as they only mess with our serotonin receptors. We can move, think, talk, we know when we need to go to the bathroom, we have no intention of jumping off cliffs, hitting or murdering other people, and similar shenanigans. What psychedelics definitely turn off, however, are the so-called connector nodes of the brain.

In order to understand the function of the connector nodes, we should ideally imagine some traffic junctions in Bratislava. If a major highway in Bratislava is closed (e.g. the city’s “Einstein highway”), drivers have to turn off their usual route, often ending up in unfamiliar territory (e.g. among the dystopian apartment blocks of Petržalka, or among the futuristic skyscrapers of Zaha Hadid in the city centre). Because there are so many roads in Bratislava, drivers will eventually reach their destination, but only after a longer and perhaps more interesting journey.

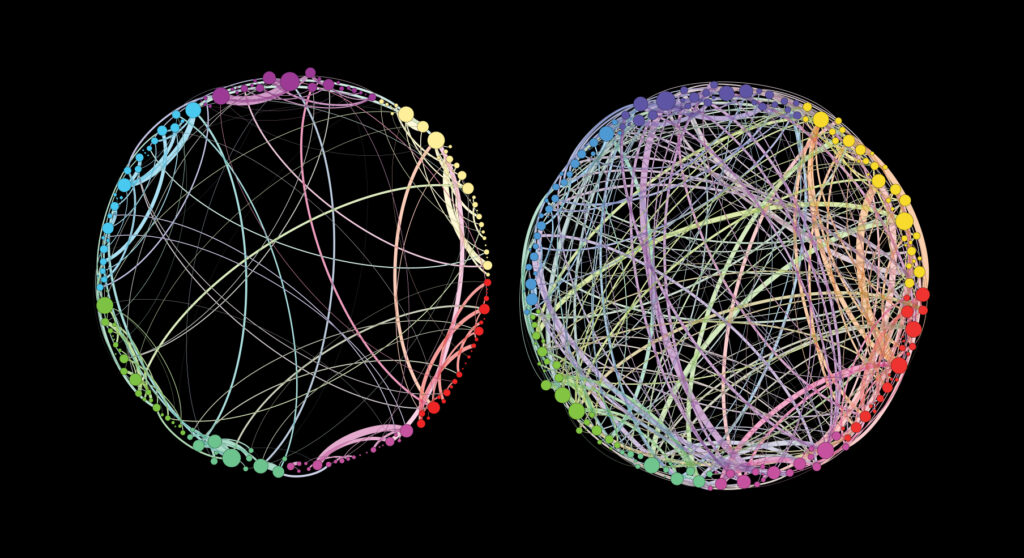

Something similar happens when psychedelics shut down the major connector nodes in the brain. Suddenly there are many more connections between areas that wouldn’t normally communicate with each other.

For example, the figure below compares the communication connections in the normal state (left) when the connector nodes are untouched and in the psychedelic state (right) when they are turned off, leading to an abundance of new communication connections between brain regions.

DMN

Perhaps many of you are asking the right question – “what is the function of connector nodes?”.

Well, whenever our brain is not engaged in a specific task, it goes into a special mode, which is the responsibility of an area called the “Default mode network”, or DMN for short. The DMN is like an integration center that organizes the data our brain works with. It is involved in self-reflection and metacognition, or “thinking about thinking”. It allows us to plan, mentally time travel, and autobiographically analyze ourselves.

Most importantly, if DMN is static and does not develop neuroplasticity (which may be due not to the absence of psychedelics or meditation, but also to the absence of a stimulating environment), it can torture its bearer considerably. Such a “static” DMN mode is actually the mythical “Old Brain” we have been talking about the whole time.

When psychedelics shut down some connector nodes, they also reduce the stability of the networks that lie above these nodes, in our case – the DMN.

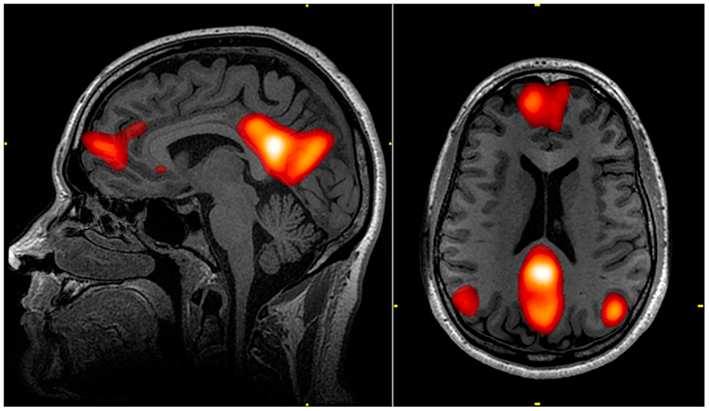

So if we disrupt the functioning of our DMN – for example, by taking a psychedelic substance – how does that change our thinking and behavior? Well, it will create an “idling” state and a “space” within it, which will create room within us to think differently! And this is where the great parallel with meditation arises – even if we look at brain scans during a psychedelic experience, we can see that the images are very strikingly similar to the state of the brain during meditation. We are creating a New Brain that is disrupting the established structures of the Old One. The New Brain is the meditative/trippy brain.

And as we already know, in such a state we literally experience reality in a different way. We don’t experience anything that isn’t really happening, but we experience it in a completely different way than what we’ve been used to. And this is why both psychedelic and meditative states are often called “altered states of consciousness.” However, although meditative and psychedelic experiences are very similar in terms of brain activity, their subjective experience can obviously differ. This will be dealt with in the next section dealing specifically with subjective experience.

Among other things, we have also observed in research that the overall communication of neurons in the brain is radically improved during the psychedelic experience. Even parts of the brain that normally did not communicate with each other suddenly became good friends for some reason and communicated in a “common” language. And that’s very interesting, because if we could pretend to be esotericists, we could say that the brain in this situation for some reason seemed to know what it was doing – the brain just cleared out some old dusty packages and remembered some old forgotten processes in the process.

And something similar undoubtedly happens to us when we meditate. The brain doesn’t just pull new ways of thinking and looking at reality “out of its ass”, it learns on its own thanks to the “space” that allows it to observe itself.

This is why psychedelics often show a remarkable effect in people who suffer from mood disorders. Mental disorders such as depression, anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) are often undoubtedly associated with DMN hyperactivity. In such cases, if the DMN activity is disrupted, this often leads to a radical and long-lasting reduction of symptoms.

Back to Patrick

You may be wondering why I mentioned a friend of mine, Patrick, at the beginning.

We know that our brains are characterized by a kind of neuroplasticity, which means that when a signal in the brain (for example, an emotion or a thought) travels down some well-trodden pathway and suddenly the pathway isn’t there because it’s not active, our brains find another one. And so we could simplify our narrative about the Old and New Brain into patterns:

Old Brain = Static DMN → Static Brain New Brain = Old Brain - Connector Nodes → Elastic DMN → Neuroplasticity

So what does that mean? It just means that when there are changes in the DMN, the brain responds with neuroplasticity, and neuroplasticity is a structural change in the brain. And as we already know from the last article on meditation; structural changes in the brain are something that allows us to think differently without being under the influence of psychedelics (or meditation practise). Due to neuroplasticity, our brains start looking for an alternative pathway and thus start forming new neuronal connections that would not normally form. And we begin to experience this change in our ordinary life just as a kind of subtle “micro-idle” that appears out of nowhere.

And for example, Patrick, thanks to this “micro-idle”, stopped identifying with his “I”.

Among other things, in the last article on meditation we forgot to mention that neuroplasticity can be divided into two subsets. Namely, the formation of new neurons (called neurogenesis) and neuroplastic changes to already existing neurons – such as strengthening or weakening of already functioning synapses and the formation of entirely new connections between neurons (called synaptogenesis). I would venture to suggest that the described phenomenon of “micro-idle” and the related “observing” or ” observing something else” is related to just both kinds of neuroplasticity, but unfortunately I don’t understand the brain enough to push a similar hypothesis anywhere else beyond pure philosophical speculation.

Most importantly, it’s not just meditation and psychedelics that have an effect on both types of neuroplasticity. Simple stimulating environments, learning, or physical activity is enough (neuroplasticity is understandably severely impaired in depressed, anxious, but also immobile or couch-potato patients). Clinically, it is important that the degree of these changes can be influenced pharmacologically; almost all antidepressants or lithium increase neuroplasticity. With psychedelics, however, it is remarkable with what efficiency the neuroplastic changes occur. And this is entirely due to the mechanism of DMN disintegration.

Subjective Experience

Now we probably know that psychedelics work like no other molecules in the brain. But how can we imagine the whole procedure of the trip in relation to our subjective perception of reality? How can we imagine the change of connector nodes and the work of psychedelics with the default mode network, and what all kinds of phases the psychedelic trip on lysergamides actually takes us through? How do you bring this experience to someone who has never experienced it in their life?

We will explain all this in this section. But before that, we will explain the 4 basic phases of the effects of any substance, which we will also distinguish in this article for lysergamides.

The first phase is onset. This phase is defined as the period that lasts until the first recognizable effects of the substance appear. It is, in short, the ‘sober’ period which lasts for some time after the substance has been taken.

The second phase is the come-up phase, i.e. the phase between the first perceptible changes in perception and the point of highest subjective intensity. This phase is also commonly referred to as the ‘coming up’ phase.

The third phase, the peak, is the point of highest intensity of the effects of the substance.

The final phase, the offset, is thus the period lasting from the peak to the completely sober state.

Onset and Come Up

Officially, the length of onset for 1cP-LSD is reported to be between 20 and 60 minutes, but the time is not that important. Onset time depends on a huge number of parameters and variables, such as the particular metabolism of the user, time and place of ingestion, dose ingested, etc.

The length of the come up is given as between 45 and 120 minutes after taking the substance. Significantly, among the frequent initial effects is a sort of heightened sense of one’s own body and a “tickling” sensation in the stomach. This feeling, in my opinion, undoubtedly correlates precisely with increased cortisol in the body, which can be hacked very well, for example, by taking ashwagandha (which is extremely helpful in lowering cortisol) before the trip.

This “nervousness” reminds me, for example, of my first childhood plane trips to Greece. As soon as I woke up knowing that we were taking off in a couple of hours, I felt my body very much and I also had a “tickling feeling” in my stomach. It was a feeling of extreme excitement and nervous cortisol shivers at the same time.

The feeling of physiological tension spreads through the entire network of the human body during the come up and transforms into a feeling of whole system tension. It is this feeling that could be characterized by the fact that the thoughts (intentions) of the Old Brain are literally amplified. It is essentially the most nervous state one can experience during the course of a pure lysergamide trip.

It is a state of total chaos and not surprisingly so. In the section on serotonin 2A receptors, we explained that during the course of a psychedelic trip, there is a massive firing of neural activity and greater inhibition at the same time. In the come up part of the trip, however, there is a large firing of neurons above all else. Hence the chaos.

Beginners in this state often tend to “recursively” loop through their thoughts. A person seized with nervousness vainly tries to figure out the source of his discomfort. The problem, however, is that as soon as one “processes”/”solves” the problem, another problem pops up in one’s head, and as soon as one begins to solve and process that one, one returns to the old problem one thought one had already solved/processed.

An interesting finding is that most of the “nervousness” during come ups is due to muscle spasms or other physical problems in the body. The final experience can also be affected by the hydration or recovery of the body during sleep, which is why many experienced psychonauts endlessly discuss the importance of “set and setting” during a psychedelic experience.

Incidentally, to get rid of bodily miseries, it is very advisable to prepare for the lysegamide trip by physical exercise; for example, some movement or yoga (of course, it is advisable to include these things in your normal life as part of your normal activity, but during the lysergamide trip the perception is expanded and the body is particularly sensitive to all stimuli).

Apart from yoga and ashwagandha, beginners can also relieve themselves from recursive loops by simply engaging in a particular activity. Recursive cycles are a manifestation of too much self-analysis (which we have just described above as the default mode network activity), and in the case of engaging in an activity, we are able to direct our thoughts (intentions) a little even during this chaotic state so that they do not analyze each other, but cooperate with each other. Although they are very good at cooperating in the tripping state, they are extremely unstable and extremely easily distracted in their work performance.

This is, by the way, a perfect hack that I recommend to apply (to some extent) to any other areas of life where you feel some source of discomfort due to too much self-analysis. Your intentions may be solving a problem, and after solving it, they will solve another problem again, but at least they won’t be analyzing you 🙂

Thus, a trip, and especially its initial phase, is certainly not an effective tool for directing attention to one particular activity.

As intentions become stronger and stronger, and also due to their increased activity, the way of perceiving during the come up is more and more visibly reshaped. The surrounding environment seems more 3D – the structures of the environment are more pronounced. The visual experience is more powerful, just as the olfactory, gustatory, tactile and auditory experiences are more powerful, but the visual is usually the first thing one gets used to notice.

The highlighted structures of all spatial objects begin to change their shape in correlation with the activity of a person’s psychological structures. The brain begins to bound objects and arrange their internal structure into fractal patterns.

Most importantly, nothing rearranged is static. The rearrangement of space changes with the view and focus, and the view and focus change with the rearranged space! At higher doses of psychedelics, the brain even borders visual objects so randomly that it doesn’t have to search for fractal patterns inside the spatial borders of real 3D objects, but can already 3D model itself directly.

In such a state of perception, familiar objects are undoubtedly different and new. With the altered perception of their visual form, their connotation of meaning undoubtedly changes as well (new neural pathways).

Sound and other senses take on more realistic contours. In such a state of tripping, the human brain’s natural need to separate itself from the perceived environment usually disappears and synesthetic experiences occur.

All the sensory perceptions flow together as they influence each other.

A friend of mine described his experience with music during a psychedelic experience something like this: “I don’t feel like I’m listening to music! The music just plays in my head,” meaning that he fully perceived how his consciousness “became” the music.

Peak

Gradually, this leads to the next stage of the trip – the peak. The peak begins approximately two hours after the initial effects of the lysergamide trip have begun and usually ends after about the fifth hour.

Just as the observed objects and senses “merge” in the end of the come-up, our thoughts somehow “merge” as well. As they merge, the nervousness understandably goes away, but the final experience deepens. Inhibitory neuronal activity begins to predominate in the brain, the “I” (and therefore the DMN) is most disintegrated, and very interesting spiritual experiences occur, during which many feel a kind of “limitless love,” or a sense of “oneness with the environment and the universe.” After all, these are not feelings that a meditation master would not feel in some peak meditative experience.

(In very intense states, it is possible to reach the peak experience of the so-called “death of the ego”, or “I observe, but there is nothing to observe”. However, if the “death of the ego” is experienced by a guy who has years of experience with meditation and various states of consciousness, he will probably process the experience quite differently than a beginner who has taken his first trip. The death of the ego is a very unusual experience, and many beginning psychonauts may get the feeling that they are really dying and start to fear for their lives. This is why all psychonaut practice should, at all times, be conducted with a considerable degree of responsibility and therefore knowledge of the substance/technique being practised).

With the meaning of connotations altered, one looks at experienced things in an extremely unusual way (and they don’t even have to be visually or otherwise altered) in the peak of the trip. He perceives them from the super-observer perspective of the New Brain.

The “dummies” in this state don’t look like the things they are meant to resemble, they look like dummies. Cultural constructs seem ridiculously primitive.

(I myself remember thinking, in the course of a psychedelic experience, when looking at a made-up woman, that she looked exactly like a monkey with paint on her face, and how much I don’t understand how such an apperience can evoke an impression of attractiveness in anyone, including the woman herself, who has put on make-up.)

Insights into ourselves tend to be just as intense and critical at this point as insights into the environment. There is a comprehensive reboot of everything and a massive inter-sensory insight. A state of absolute running out of one’s established structures and a state of dissolving the patterns between which there has been constant iteration.

Offset

The intense state of the peak of the trip will begin to slowly subside and transition into the final third phase of the trip, which is called the offset.

Understandably, once the feeling of total dissolution of the “I” and unification with the environment subsides, one “returns” back to some of one’s old structures. Cultural constructs no longer seem so highly ridiculous and primitive to him, since one also begins to be determined by them.

But most importantly, a large part of the person has remained altered and rebuilt. A person returns to his “old self” only in part because of the ongoing changes in his brain (many dummies will remain dummies, many cultural constructs will remain primitive, and even many made-up women will remain incomprehensible).

People often enjoy the new state and their joy does not fade even after the last effects of the trip have passed. They can’t wait to play around with the mental conditions and try them out on the many different environmental trappings. It’s reminiscent of the state when a child gets a new toy for Christmas. He or she enjoys it the next morning, maybe even the next few days, until they get completely used to it and live with it.

This condition is undoubtedly linked to the integration of the experience itself into everyday life and to neuroplasticity. In English there is a term for this, ‘afterglow’, which refers to a long-lasting, often lifelong, change in the perception of reality caused by the psychedelic experience. Again, this is something that can also be achieved through long-term meditation practice.

Of all the effects of the trip, it is the state of visual or other sensory change that ultimately remains (but the visual is usually the most visible, as we have already mentioned). The actual 3D-modelling and rearrangement of the spaces of the brain usually disappears after the peak (which also depends, of course, on the intensity of the experience and on the amount of substance administered) and turns into merely an arranging of the internal structure of the objects based on their somehow default boundaries in reality. This state of visual searching for fractal patterns can easily exceed the twelve-hour limit from the beginning of the tripping.

In such a state of offset, despite clearly not missing all the effects of the trip, the tripper feels fully sober. In this state, any feeling of nervousness has passed and a sense of relief sets in, often accompanied by increased dopamine.

Conclusion

Sometimes a few meditations or one more powerful trip is really enough to make a complex change, but many times it is not. Neuroplasticity and the New Brain is largely a manifestation of integrating these experiences into ordinary life. And hence mainly the “micro-idles” and the new neural pathways that the micro-idles trigger. Working with your own brain is a tough nut to crack and requires a lot of effort, but also a lot of intelligence.

And while I try to be an optimist I won’t hide the fact that I regret how free I felt while writing the last article about meditation and how un-free I felt while writing this blog. I had to carefully consider every word and add a disclaimer to the beginning of the article to make it obvious that I am not trying to “promote drugs” here.

Psychedelics, because of many years of political propaganda and machinery in our society (but also because of the many morons who have popularized them in not exactly the best light), have the status of a “drug”, that is, the status of what we are supposed to be afraid of and what we can use to harm ourselves.

However, as I mentioned in my last blog, everything around us is just a tool, and the functionality of the tool depends on the way we use it.

I firmly believe that it is education and proper evaluation of all possible and impossible risks that will help us see tools (not just psychedelics) as they really are and break down all their nonsensical status quo and narratives. And indeed, we can be thankful that our Western society now perceives psychedelics much better than it did, say, twenty years ago. And we owe this primarily to education enthusiasts, scientists and therapists.