In my article on clients and replacements for classic social networks, we mentioned something about how encryption is far from the only guarantor of self-defense against Big Brother.

This time, we’ll also look at security and protecting our privacy, but from a slightly different perspective. We’ll explain how you can protect yourself from Big Brother using browser extensions, but we’ll cover those specifically in part two of this series.

However, to understand the topic and why protection makes sense at all, we should first know how far Big Brother reaches and how it is possible for him to access our data. And also which data Big Brother likes most.

So in the first part, we’ll look at fingerprinting and cookies.

Browser Fingerprinting

In order to understand tracking and Big Brother, we must first understand how “browser fingerprinting” works. This term means nothing more than tracking online activity and identifying individual browsers and devices.

Browser fingerprinting is a sketchy, accurate method of identifying unique browsers and tracking online activity. Fortunately, there are many simple ways to avoid browser fingerprinting, but let’s first take a look at what browser fingerprinting actually is.

Wikipedia defines browser fingerprinting as follows:

“A device fingerprint, machine fingerprint, or browser fingerprint is information collected about a remote computing device for the purpose of identification. Fingerprints can be used to fully or partially identify individual users or devices even when cookies are turned off.”

This means that when you connect to the internet on your laptop or smartphone, your device passes a lot of specific data about the websites you visit to the receiving server.

Browser fingerprinting is an effective method that websites use to collect information about your browser type and version, as well as your operating system, active plugins, time zone, language, screen resolution, and various other active settings.

This data may seem quite general at first glance and may not give the impression that it is customized to identify one specific person. However, there is a significantly small chance that another user will have 100% identical browser information. For example, Panopticlick found that only 1 in 286,777 browsers will have the same fingerprint as another user.

And where exactly can we find a parallel with Big Brother here?

Well, the uniqueness of the browser information is kinda related to the investigative method of police and forensic teams identifying suspects and criminals based on fingerprints at crime scenes.

The Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System (IAFIS) is a huge database that stores the fingerprints of 70 million subjects from criminal cases as well as 31 million fingerprints from civil cases. This means that a large proportion of these fingerprints have been collected for the purpose of analysis.

And that’s sort of how browser fingerprinting works, too. Websites collect large amounts of visitor data in bulk so that they can later use it to compare it with the browser fingerprints of known users so far.

The international advertising industry and marketing machines love our data. Data tracking and collection methods are extremely valuable because they allow advertising companies to build a profile based on your data. The more data these companies have, the more accurately they can target advertising at you, which (indirectly) means more revenue for the company.

Methods for fingerprinting/tracking

In the following sections, I will provide you with information about how websites communicate with your browser and how they obtain information. Our lovely cookies are largely responsible for this, but cookies are not the whole story. We’ll get to the details later, though.

Cookies

A common way in which websites collect your data is through the use of cookies.

A lot of people sort of “suspect” that cookies are something very bad and ask me how cookies could be avoided at all.

But what exactly are cookies and are they really that evil?

Let’s start first with a history and general characteristics. An HTTP cookie is a label for a small amount of data that a website stores on a user’s computer via their web browser. It is a standard feature contained in the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP), which has been in use since June 1994.

Its author is Lou Montulli, an employee of Netscape (formerly dominant web browser). Montulli created cookies in the early 1990s in order to work on the development of an e-commerce application. At the time, Montulli found that it would be very useful to have the ability to remember a particular specific user without having to log in and fill in their details anywhere. Well, that’s how the cookies that almost all e-shops use today were born.

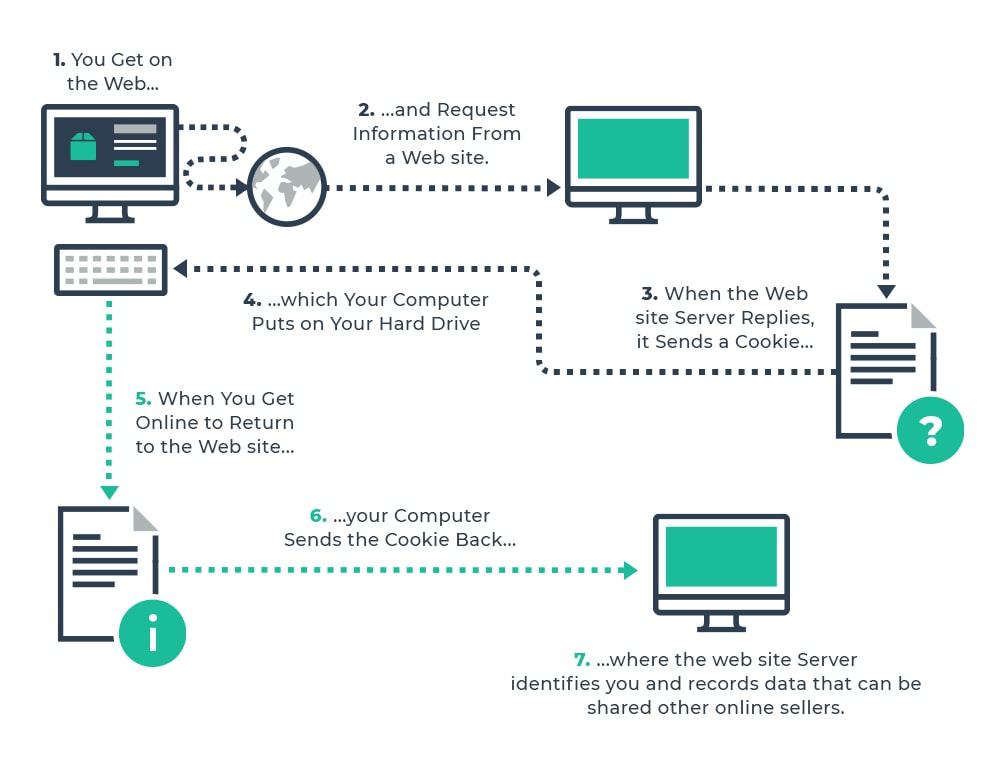

And how do cookies work?

A cookie can either be created by the server (and sent to the browser along with the generated page in the form of an HTTP header), or by the browser itself when interpreting the page using JavaScript.

In practice, this means that the web server transfers a snippet of JavaScript code to your browser (the browser then stores the cookie somewhere on the disk of the web visitor’s computer, usually in a temporary files folder). Your browser executes the code locally and the code happily collects the data. For example, it collects your screen resolution, hardware, IP address, time zone, browser type, etc. The JavaScript then creates a hash of your data (browser fingerprint) and sends it back to the server – cookies are then transferred whenever information is exchanged between the server and the browser. The most traded fingerprint data are mainly bank details, insurance details, personalised ads, etc.

In addition, JavaScript can interact with visitors in order to perform certain tasks, such as playing a video. These interactions also generate a response, and therefore, again, some information about you is gathered.

Types of cookies according to their lifespan

There are two basic types of cookies – session cookies and persistent cookies – depending on how long they can exist.

Session Cookies

Session cookies are cookies that are deleted as soon as your session ends. This means that cookies disappear as soon as you close your browser window and are not stored anywhere – your browser recognises such cookies, due, for example, to the fact that they do not have an expiration date set. We owe this kind of cookie, for instance, to the fact that our products remain nicely in the shopping cart even if we have closed the shop’s website (but not closed the browser).

Persistent Cookies

Persistent cookies, on the other hand, have a set expiry date, such as two years after you visit the website. However, this date can be postponed for each subsequent visit to the website.

This is exactly how the cookie called _ga works, which Google Analytics uses to “measure” its specific visitors. This is why persistent cookies are sometimes also called “tracking cookies”.

Types of cookies according to the founder

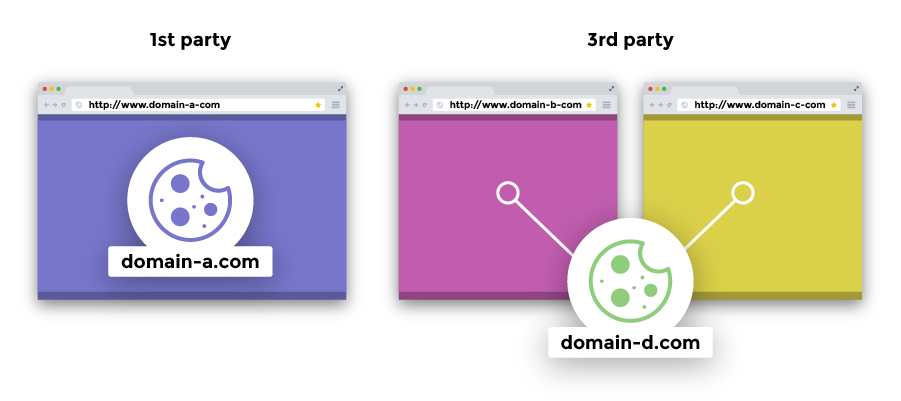

Depending on who set the cookies, they can be divided into 1st Party and 3rd Party Cookies. Technically, both types of cookies are more or less the same, collect the same types of information and perform the same functions, but they differ in how they are used.

1st Party Cookies

1st Party Cookies are mainly used to enhance the user experience on the website.

They are transmitted by a script that runs on the host domain (the website you are visiting and that you see in the address bar of your browser). These cookies are considered quite uncontroversial and secure, better able to pass through various firewalls and the stricter security rules of some browsers (e.g. Safari).

Websites create 1st Party Cookies almost every time you visit them, but in some cases some computer scripts may also create them directly. Either way; 1st Party Cookies are unique to each website.

Although 1st Party Cookies perform a variety of tasks, for simplicity we can break them down into three basic categories that everyone is very familiar with:

- Greeter – this 1st Party Cookie recognises you when you visit a website and allows you to log in using your login ID and password.

- Shopping Cart – remembers all the items you put in your cart or wish list.

- Personal Shopper – sees what you like and recommends other items for purchase based on your preferences.

3rd Party Cookies

3rd Party Cookies are already created by parties other than the website owner. These are mostly tracking cookies created by advertising companies. Tracking them allows you to see ads for products similar to the ones you are buying.

3rd Party Cookies are used by companies that want to advertise and sell you goods.

Here’s a list of some of the types of companies that leave cookies on your browser to track you:

- Ad-retargeting Services – create small cookies that capture you when you visit a website with the same cookie code. They then track you across the internet, see where else you look, and generate ads for their clients in your browser.

- Social Media Plug-ins – link you, link the page you visit and link that page’s social media account. Not only do they set up a connection to Pinterest or YouTube, but they also start following you and can monitor your use of that social network.

- Chat Box Pop-ups – offer to help you if you chat with a bot. Such cookies are usually session cookies and should therefore disappear whenever you close your browser.

3rd Party Cookies are not necessarily problematic, but can cause problems if used in a way that collects and uses data without direct permission.

In terms of “usefulness”, I divide four basic types of 3rd Party Cookies:

- Helpful Cookie – this 3rd Party Cookie is a file that you would probably agree to if given the choice. It is a cookie that can bind you to a program running on a website that allows you to morph your face into animal faces, for instance. It may be a chatbot or other program sold to the creator of the site.

- Sales Cookie – it’s an unlimited tracker that is used to create targeted advertising (and therefore show you ads for the items you search for).

- Shady Cookie – the purpose of this cookie is to track you on the internet and collect bits of information about you. The cookie then combines this information with other cookies that contain identifying information. The goal here is to sell your information to other companies, presumably for the purpose of selling you goods that you may not even know about.

- The Villain – this 3rd party cookie is very mischievous. It plans to do something you wouldn’t like. Several of them will be identity thieves. Some of them are stuffing feeds on your social networks with bullshit. The thing to remember is that a single pixel in an ad can contain a 3rd Party Cookie and pass it to your browser!

What about 2nd Party Cookies?

If there is a first and third party, there should be a second party, right? Yes, there are 2nd Party Cookies, but their purpose is much more limited. Such cookies share data between three entities – the consumer, the website the consumer has visited and the website’s partner(s).

2nd Party Cookies are primarily used in data sharing agreements, although their use is not very popular. Many of them represent data collection partnerships.

They are only useful for internet marketers who are also data brokers.

| First-party cookies | Third-party cookies | |

| Who made the cookies? | They come from the webpage publisher. Can be JavaScript code or part of the website’s server. | Ad servers and other servers load them onto your browser. They do not come from the main website you visited. |

| Where are the cookies used? | Only work on the website that made the code. | Accessible on any website that loads a third-party server’s code. |

| Who can read the cookie? | Only the original website can read them. | Anyone with the correct program can read them. |

| When can the cookie be read? | Only when the original user is actively on the original website can they be read. | Users can read them at any time. |

| What does my browser do with them? | Supported by all browsers. Browsers give users tools to reject cookies. | Once supported by all browsers. However, browsers are increasingly blocking them or providing ways around them. |

Cookies in the future and Cookie Laws

1st Party Cookies will be around for some time to come because both the website and the people who use them benefit from them. One day, however, maybe someone will develop a better way – a more elegant way to fulfill their function.

We are not going to deal with the law very much here, as the legislative situation is constantly changing. However, we will mention a few key points – the ePrivacy Directive (ePD), the EU’s directive on data protection and privacy in the digital age, was issued back in 2002 (but it is questionable how effectively the ePD works at all).

EU regulators then tightened regulation and in 2016 came up with the General Data Protection Regulation, known as GDPR.

In 2021, an opt-out/opt-in obligation was created, i.e. an obligation to obtain free, informed and unambiguous consent to the storage and processing of all cookies that are necessary for the operation of the site.

For example, Google has announced that it will phase out the use of 3rd Party Cookies between 2022 and 2023. Instead, it is exploring ways to use ads more openly and “honestly”.

So 3rd Party Cookies are slowly disappearing. This is partly the work of European regulators (who have been joined, for example, by the Californian government), but more importantly, most modern browsers already block them.

In addition, modern browsers support other ways of storing data such as cookies:

- localStorage – it is a browser repository that is accessible using JavaScript. Data is stored here “forever”, it does not have a limited lifetime (as is the case with cookies).

- sessionStorage – is the same as localStorage, but its contents are deleted when the browser is closed. So it works the same as session cookies.

Simply put, the benefits of alternative data storage can be as follows:

- larger data storage,

- do not slow down communication with the server,

- easier to work with.

The disadvantage of these alternative technologies may be that the data does not reach the server automatically. However, they can be used for web analytics or user authentication. However, if you need to store data for offline web use or are concerned with personalization, localStorage or sessionStorage are excellent substitutes for cookies.

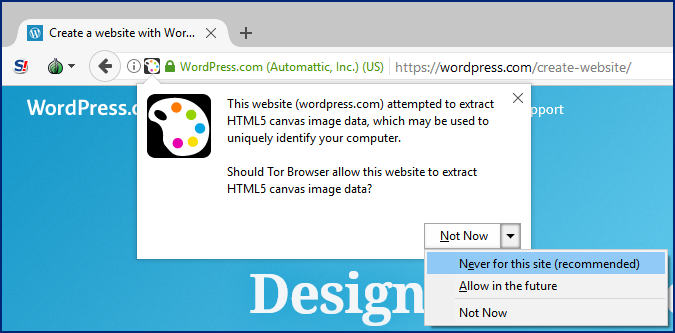

Canvas fingerprinting

Canvas fingerprinting is, at the time of writing (2022), quite new in the field of browser information retrieval, and is quite an interesting and elegant way of tracking.

How does canvas printing work? Simply put, web pages are written in HTML5 code and within that code is a small piece of other code that takes your browser fingerprint.

HTML5 is the coding language used to create web pages. It’s the core basics of any website. Within the HTML5 coding language, there is an element called the “canvas”.

Originally, the HTML <canvas> element was used to draw graphics on a web page.

Wikipedia provides the following explanation of how the use of the HTML5 canvas element generates browser fingerprints:

“When a user visits a page, the fingerprinting script first draws text with the font and size of its choice and adds background colors. Next, the script calls Canvas API’s ToDataURL method to get the canvas pixel data in dataURL format, which is basically a Base64 encoded representation of the binary pixel data. Finally, the script takes the hash of the text-encoded pixel data, which serves as the fingerprint.“

hat this means is that the HTML5 <canvas> element generates certain data, such as the font size and active background color settings of the visitor’s browser, on a website. This information serves as the unique fingerprint of every visitor.

n contrast to how cookies work, canvas fingerprinting doesn’t load anything onto your computer, so you won’t be able to delete any data, since it’s not stored on your computer or device, but elsewhere.

Test your browser

There are various tools available that make it possible to test your browser identity. You can use “Am I Unique,”, “PANOPTICLICK” or “Unique Machine“.

Each of these tools will check your browser’s fingerprint and evaluate how unique your data is.

The Am I Unique tool uses a comprehensive list of 19 attributes (data points). The most important attributes include whether cookies are enabled, what platform you are using, what type of browser (as well as version) and computer you are using, and whether you have tracking cookies blocked.

On the Am I Unique website, just click “View my browser fingerprint” to start the test.

Conclusion

We already know how tracking works and what happens in the background. This article was not meant to moralize over anything or to judge whether tracking is “good” or “bad”. It was only meant to explain what and how it works.

Although in the article I referred to only the collection of data by companies as “Big Brother”, it is important to remember that not only companies that send us advertisements may have access to data (we spoiled Europeans are usually only used to this standard). Data is data and can be handled by anyone who gets their hands on it. Whether it’s one sneaky guy in a hoodie with a laptop, or a supermassive government spying on citizens (the Chinese could tell us a bit more about that). Our data is first and foremost ours, and more or less protection therefore can’t hurt.

We don’t actually need any fingerprint analysis to know that there is no complete protection against browser fingerprinting. Some parts of fingerprinting can be protected against by, for example, VPN or Tor (which can hide our IP address), by choosing a specific browser (with its own cookie and tracking policy) or even by a simple anonymous window. Deleting history and deleting cookies is also a good idea (in Firefox, for instance, all cookies are automatically deleted as soon as you end the session), and it’s also worth being more careful when surfing Big Brother social networks.

However, in the next section of The Wall Against Big Brother, we’ll explain how to protect yourself from tracking of various kinds a little more comprehensively and yet quickly and easily using browser extensions.

Among other things, an earlier version of Panopticon recommended downloading an extension called Privacy Badger to increase your privacy on the Internet, which we’ll (also) cover in the II. section.